When you’re picked as a child, you think you’re important.

Whether you’re selected as Daddy’s Girl or Momma’s Boy, a parent’s or caregiver’s confidante or punching bag, as the chosen child even its own mother wouldn’t feed, when you’re “it,” you think you have extraordinary importance and power.

It’s a bitter irony that when purposely selected – for physical, sexual or emotional abuse – or when neglected or deprived, when purposely not selected for care – you thinks it’s for a reason. And selected children believe they, themselves, are the reason. They believe they are singled out because something about them makes them uniquely deserve too much involvement or not enough.

It’s a bitter irony that when purposely selected – for physical, sexual or emotional abuse – or when neglected or deprived, when purposely not selected for care – you thinks it’s for a reason. And selected children believe they, themselves, are the reason. They believe they are singled out because something about them makes them uniquely deserve too much involvement or not enough.

You think you’re the best. Or you think you’re the best at being the worst.

Many survivors of sexual abuse are at war within themselves because they reject the violation, but remember the feeling of personal closeness, the physical pleasure, the feeling of being especially chosen.

An adult who uses or neglects a child has an open chasm of need. Again and again, the child throws its small self into that black chasm. No matter what the child does, that chasm is not filled. The child flails, falls, fails. Selected children learn that they are flawed at every level of being and doing.

Addiction support groups overflow with people in agony over the paradox of feelings of self-importance and self-loathing.

I have been wondering about my own self-hatred. Why in the world do I have such capacity to love and accept others, to empathize with them and feel such compassion for them – but not for myself? What standards am I trying to measure up to that I’m not meeting? It doesn’t make sense.

When they were both 25 years old and I arrived as their daughter – for their own reasons for them to tell or not to have told, their choice – my mother and father had extraordinary needs and wants and expectations and visions for me and for my life and what I could do and mean for them. I look at photos of myself as a baby. In many, I am unsmiling. Could I have known already what the deal was?

Be best at everything for everyone. That’s how to get love.

“I’ve tried my whole life to please you,” I said to my mother. “No you haven’t,” she replied.

Over a half a century I have tried to be great enough to get love. On her deathbed, my mother was still disappointed with me. My father is over 80 and still primarily unhappy. I have failed at two marriages. And now I’m an alcoholic.

I give up.

I have thrown myself over the cliff, flying spread-eagled into black chaos of the chasm of needs and wants and expectations of others for the last time.

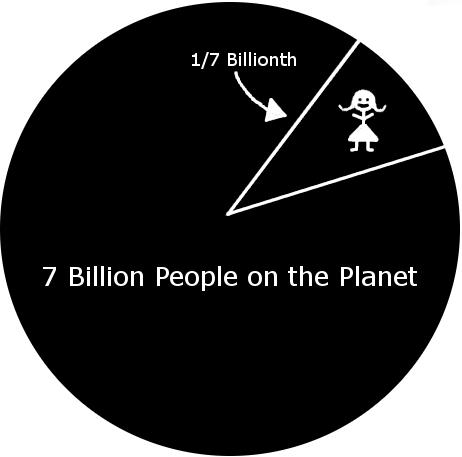

I was appointed to the position of being great. I did not volunteer to save the world. I am not the heroine, the protectress, the savior, the great teacher, the great lover, the ultimate daughter. I don’t want to strive to be extraordinary out of the 7 billion people on the planet. I want to be 1/7 billionth. I want to belong, to be one of many. I don’t want to be an isolated outlier, straining to be best. I’m just one person, one woman. I can do some things for some people some of the time. But no way can I be anyone’s everything. No way can I figure out what everyone needs and wants and what would be best for them and provide it. At that I flail and fall and fail.

Most addicts and alcoholics have trauma, abuse and/or neglect in their pasts. Ill-treatment during childhood is paired with narcissism and grandiosity. Addicts are notoriously difficult to get into treatment of any kind. If they ever do accept help, they have trouble staying with it once they start, or sticking with it on any consistent basis.

Addicts and alcoholics say, “I can do this myself,” “I don’t need help,” “I know what I’m doing,” “I don’t agree with that program,” “I know that kind of treatment won’t work.”

At essence, they’re saying, “I’m different.”

And why wouldn’t they? Being singled out makes you different.

Graphic by Laurel Sindewald

It is liberating to be able to acknowledge that we can never fill another’s void. That is their own existential struggle. All we can do is recognize it, be kind to one another, and meditate on what is fulfilling for us. I’m beginning to think that the greatest way to help someone is to leave them in their void and let them pull themselves out- or not! We can try, but we can’t do the work for them. We can only keep them company, and maybe be a mirror so they can see themselves more clearly. They have to see where they are and have a desire to “be” elsewhere.