Let’s see. To quote poet Peter Meinke, where was I “before everything got written so far wrong”?

Oh, yes. It was July, 2006, and I was finishing an internship in addictions counseling, completing a master’s degree in counseling, and packing up my little townhouse in Tampa for a move back to my hometown in Blacksburg, Virginia, where my parents still lived. My mother was ill, my attempts to live the life I thought I was supposed to live – a melding of Cinderella, Barbie and Betty Crocker – just hadn’t worked, and I was ready to head home, help my mother and father, and start a new life.

I felt solid and strong at 47 in a way I had not felt since college. In my late teens and early twenties, I felt as if I were living the truth of who I was. I was raised in Blacksburg, home of Virginia Tech, and when I arrived as a student myself, I gloried in learning, reading, studying, writing, and discussing. I lived in the dormitories and ate in the dining halls all four years, surrounded by people my age. I asked the department secretary for a list of faculty members and systematically met with each one, adding check marks to my mimeographed list. My kind and smart boyfriend also treasured scholarship. I lived with connection, passion and peace.

Going to college was expected in my family, as was getting married. My boyfriend and I broke up during our senior year and I soon met and married a good man from Tampa and we moved there.

Having a family was expected as well. Three years into our marriage, we began to try to conceive a child. He was perfect. I was not. After a few years of fertility drugs and procedures, I became too heartbroken to try any more. Many marriages don’t survive the loss of a child. I immersed myself in my work as a teacher to move away from grief and I moved away from him as well. He hung in there heroically for many more years but we eventually divorced. I had been in Tampa and away from Blacksburg for 23 years.

But by July, 2006, I had faced my demons. I had been in counseling for childlessness and to recover from the divorce. I had self-confidence when things were going well and self-reassuring skills when they were not. I was ready to go home – to safety, to sanctuary, to a fresh start.

One month later, in August, 2006, I was at my new teaching job in a new school in lockdown with eighth graders while a fellow Blacksburg High School graduate escaped from prison and started shooting people on the town’s walking path.

A few days later, I was called to a meeting to learn that fellow teacher and family friend had been arrested for molesting children for thirty years.

Six months later, in February, 2007, an eighth grade student in the school system of which I am a graduate entered my classroom after the lesson had begun and, as he walked by me, shoved me off balance.

Two months later, on April 16, 2007, I was in lockdown for approximately eight hours with eighth grade students at my new school, a few miles from Virginia Tech, while a fellow Hokie shot our fellow Hokies and their teachers and himself.

Five months later, a student positioned himself in my classroom so only I could see and hear, looked me straight in the eye, and said in a low voice, “I’m going to shoot you.”

I was undone. Unlatched. Unclasped. I began to turn end over end over end.

. . . . .

I found the post below, dated October 10, 2012, on an old blog. I would have driven home from that event and had glass after glass after glass of wine. I didn’t stop drinking alcohol until December 28, 2012, almost three months later.

“…and the congregation averted its eyes.”

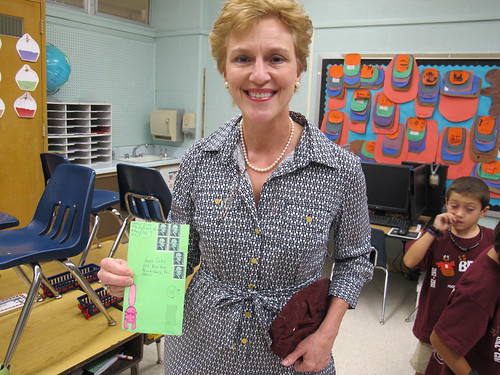

– J. K. Rowling, The Casual VacancyThe woman in the photo could be a resident of Pagford, the fictional village in J. K. Rowling’s new novel The Casual Vacancy. The woman vibrates with ambivalence. She hopes the bright pearls and bright smile will distract the photographer from her tear-reddened eyes, the loose, lined skin on her face, the way she clutches and offers mementos from her childhood as if they are precious and matter. When the woman saw the photo online, she felt the horror of a realization had too late, fists clenched, arms shaking with the desperate wish for just one more moment to do something, anything to unback the car from the parking meter, to unpour the boiling water from the shattered glass pitcher, to unclose the car door on the child’s hand.

She wanted to save the elderly woman in the photo from the inevitable: people will increasingly perceive her as inconsequential because she won’t have time to finish what she starts, or, more immediately, the strength, wits or wherewithal to do much of anything well. The rah-rah about aging is darling but changes nothing of the truth that one is increasingly less than one was and dies in the end.

. . . . .

Only in the past few years have I heard the adage about fiction, “It may not be factual, but it’s true.” I felt at home in Rowling’s Pagford, not because of its familiarity, but because of Rowling’s relentless candor.

I was raised in Blacksburg, Virginia, home of silence. Of the two suicides of my classmates, two deaths by car wrecks, and deaths of three of their parents that occurred in the years I attended Margaret Beeks Elementary School and Blacksburg High School, not a word was spoken by my parents, by my teachers, or by my classmates. The odd behavior of the swim club manager was not mentioned. Faces of the “poor kids” in the class photos from my elementary school years were missing from my high school yearbook. About loss and absence and its accompanying confusion and pain one did not speak in Blacksburg.

In Blacksburg, at Virginia Tech, I fell in love and married and moved away. I expected to have a baby, stay home and raise the baby, have another baby, and live happily ever after as a family. Only when I was unable to conceive a child and looked in anguish and bafflement at a future for which I had no ability did I see how silence had disabled me. The pain was greater than I was. I cannot remember the moment I first spoke, but only then did a slip of a self come forward. Only then did I feel a chance to not be broken by pain.

Rowling’s characters break each other’s hearts. They long to undo the undone. Then they do again, blindly and knowingly. They are alternately hurtful and calculating, brave and foolish, merciless and merciful. They and I are one. And they must, as I must – or choose not to – live with what what’s happened to us and with what we’ve done.

I find it excruciating at times to not be a member of the congregation, especially now that I’m back in Blacksburg, to not avert my eyes from the truth of who I am, from what I am feeling and thinking and remembering, from what I see when I look at what others feel, think and do or have done to them or have happen to them. I can feel upset, weak, vulnerable, even traumatized at the time of the looking. But I know, paradoxically, that I strengthen myself for what is and what will come from every truth I muscularly embrace. I live as fully as I can, not partially. On my deathbed, where it all must end, I will not regret not having tried to wholly live my life. I will not regret my silence.

I am the ambivalent woman in the photo.

Photo credit: Travis Williams for The Roanoke Times

Photo embedded from The Roanoke Times’s The Burgs flickr stream, part of the photo slide show accompanying Memories mark Blacksburg school’s milestone, October 6, 2012, The Roanoke Times.

The post you wrote those few years before is very powerful. It speaks to the exponential effect of traumas unresolved and the surreal feeling of having things go on around you that no one talks about. I feel the pain of the woman in the photo and am almost immobilized by it until I remind myself that it isn’t me, and it isn’t now. That is one of your many talents, Anne: to take the reader and place her firmly in your shoes and in her mind and heart.