“What if nothing’s wrong with you?”

– My father

In a short story I read as a teenager, aliens performed vivisection on an abducted human man and reconstructed his brain, nerves, muscles and bones so that every thought and every movement created pain. Then they dropped him back off at home.

That has been my conception of having alcoholism. My first drink was my own doing. But after that, something was done to me against my wishes, against my will, and I ended up unlike anyone I’ve ever known. On the comforting bell curve of the human condition where I treasured my place as one of many because everyone fits somewhere, I felt thrown to the edge of the paper.

After three years of abstinence from alcohol, some cognitive functioning is returning. I am remembering who I used to be a decade ago before I started drinking. But who is this aching, pale entity inhabiting my body? Something’s been altered, distorted, changed. O, how I miss you, my former self! And the merciless pain. How did this come to pass?

. . . . .

I’ve been studying the work of Pauline Boss, particularly this book, and her conception of ambiguous loss – “an unclear loss that defies closure.” A researcher and therapist, she began working with families of soldiers missing in action during the Vietnam War, then continued with those who had a person in their lives physically missing but present in thought, and then with those who had a person physically present but psychologically absent through a cognitive impairment. In people with both losses, she discovered a complex grief and chronic sadness. How is a person to handle both presence and absence, the push-pull of hope for having, plus the doubt of never having again?

“Hold on and let go.”

– Pauline Boss

What if, as my father asked me, nothing is wrong with me? Boss writes, “Ambiguous loss is a relational disorder and not an individual pathology.” I had a colleague tell me about 35 years ago, “You’re the loneliest person I’ve ever met.” What if I’m not an outlier, but experiencing a deep, unclosed, on-going grief? What if I’ve just been very sad for a very long time?

. . . . .

We timed it perfectly. I was a teacher and if my husband and I waited until fall to conceive a child, I would have the summer off with our newborn. In October, 1986, I would stop using birth control. Delight in each other began us in September but I didn’t conceive that month so our plan was safe. We picked out names for a girl and a boy and I began to buy baby clothes – a pastel green onesy, a darling twosy with orange duckies. I began to love that girl and that boy.

I never did conceive. I see by the display on the corner of this computer screen that I have been missing my babies for 40 years.

. . . . .

Part of what I lost when I couldn’t have children was my identity. I thought I was a full-blooded, fertile woman. I became a wisp of hay, neutral, neither female nor male.

The corpus of who I want to be and think I am keeps getting carved away.

I was a married woman; when my marriage ended, I was a spinster.

I was a master teacher, a champion of ideas; when the student shoved me in my classroom, the trauma felled me. I was a cowering victim.

I was a person with a sacred sanctuary within; when I developed alcoholism, I lost what makes me a self. Nora Vokow writes, “People suffering from addictions are not morally weak; they suffer a disease that has compromised something that the rest of us take for granted: the ability to exert will and follow through with it.”

With the help of others, I became abstinent from alcohol. I am not free or safe but continuously besieged from within.

The pain is unbearable.

And yet I long to live.

If I showed my “me and not-me” list to Pauline Boss, I believe she would say my thoughts are understandable, but they are examples of “either-or” thinking – it’s either all good or it’s all bad – and a source of anguished suffering. She urges people living in the presence of absence to cultivate “both-and” thinking. I have to step farther back, open my arms wide, live deep, and accept what happened then and this happening now. I have to accept that I both was and am. I must grow my heart and mind to be present for the whole of it.

Pauline Boss counsels, “To stay in control, differentiate what you can control from what you cannot. When you’ve tried everything, and there’s nothing else you can do, go with the flow. Embrace the ambiguity. Know that the world isn’t always fair – that things don’t always go your way and that this isn’t your fault. You’re doing the best you can.”

Yes. With the both-and, push-pull of me and not-me, I am doing the best I can.

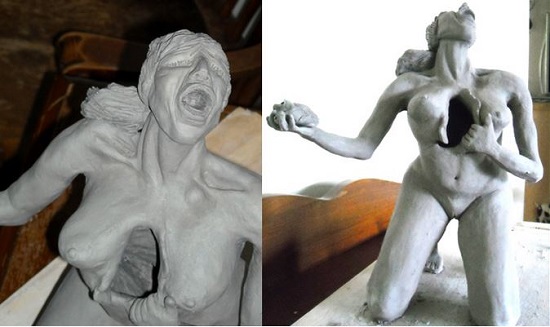

Image: Untitled by Trish Shelor White, a founder of Choices Recovery Center