Let’s suppose that, against all the odds against it, and due to the likely trauma that preceded it, unfortunate mental illness that accompanied it, and financial and social misery that predisposed you to it, you develop an addiction to prescription pain pills.

If you are addicted to pain pills, you’re likely to be among the 75% of Americans who got the pills from a friend or family member, not from your doctor. Your brain has learned that they uniquely do what needs to be done for you, in ways that are unique to you, such that a turn happens – still a black box of mystery in the brain, even to neuroscientists – and you realize you can’t stop taking the pills. And you’re experiencing negative consequences from continuing to take them. Let’s stretch the odds even further – perhaps you’ve even ended up injecting heroin.

My name is out there as someone to call. Let’s say you call me and say, “Anne, I have a problem with opioids. I’m ready to stop right now. Can you help me?”

If you stop now, I have just under 12 hours to get you help before you start going into withdrawal. Withdrawal is “uncomfortable,” not fatal? Try unremitting vomiting and diarrhea for 48 hours or more and see if you survive.

I’m a Virginia Tech Hokie, and a Good Samaritan, and an American. We don’t let our people suffer like that.

The top two treatments known to cut the death rate by half or more for opioid use disorder are methadone and buprenorphine. Buprenorphine is commonly known by the brand name Suboxone.

Started on either one, ASAP, under medical supervision, with additional medications for symptoms and other conditions you might have, you can go through withdrawal and continue with this life-saving treatment.

In our town, I can’t get you methadone or buprenorphine, the top, evidence-based treatments for opioid use disorder.

Although research-backed to result in decreased social costs compared to abstinence-based treatments, methadone has been tied up in federal legislation for decades and can only be administered at a federally regulated clinic. A prescient local doctor tried to open a methadone clinic in 2006 in Blacksburg and was shut down. A need for evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder has existed here a long, long time.

But buprenorphine can be dispensed at pharmacies, so you should be able to get a prescription from your primary care physician, right?

Federal law requires that physicians be certified to prescribe buprenorphine. They’re permitted to treat only 275 patients at a time. What that means is that you have to get in line behind every one else. Wait lists in our area are 6 months or more. In some rural areas, wait lists are a year.

If you can pay $500 cash for the first visit, and $180 per month after that – and, if insurance doesn’t cover it, an additional several hundred dollars per month for a prescription for buprenorphine – you may be able to be seen in one to two weeks at a local addictions medicine clinic that doesn’t take insurance.

So where does that leave us if you call me and ask me for help? I can’t get you methadone today or maybe ever, locally.

I can’t get you buprenorphine either. Even if I take you to the ER, they won’t administer it or prescribe it. I might be able to help you get into the private clinic in a few days, or on a 6-month or more wait list at a social services agency, although there are lots of hoops to jump through to get on a wait list, or to stay on it.

I can’t keep you stable or introduce you to treatment at a safe injection site because we don’t have any.

What if this scenario weren’t about you, but about your child? Let’s say he or she has an opioid use disorder. What can you and I do for that child right here, right now, in Montgomery County, Virginia?

We can call the two closest rehabs, one 45 minutes away, the other an hour and a half, and see if they have beds available in the next 12 hours. (Evidence is inconclusive on the efficacy of rehab.) However, administering buprenorphine at either facility is non-standard and occurs on a case-by-case basis. Patients administered buprenorphine are tapered before they leave. That puts them at an 80% chance of relapse. The barest minimum recommended time to be on buprenorphine is one year. Many people with opioid use disorder need to be on maintenance medications for life, just like many people with diabetes need to be on insulin for life.

Abstinence is not a treatment for substance use disorders.

Addiction is a medical problem requiring medical care. When your children with opioid use disorder leave rehab without medication, they’re not receiving treatment for it. Because their tolerances have dropped, they are at high risk of not only relapsing, but overdosing and dying.

Other than trying to find a rehab bed for your children, there’s nothing you or I can do to help your child stop using opioids right now.

Nothing legal, anyway. Can you imagine being a parent and saying to your child, “Keep using, honey. Keep swallowing pills into that precious body I held close to my own body when you were a baby. Keep breathing that substance in. Since you were tiny, I’ve watched to make sure you were still breathing while you slept. Keep injecting into your precious arm or hand or thigh. You might die if you don’t.” Or, “Honey, do you know someone on Suboxone that we could buy it from? Just until we can get you to a doctor?”

This is called the Heinz dilemma, used in ethics classes everywhere, to show the misery of two miserable choices. Should Heinz have broken into the pharmacy to steal the medication that would save his dying wife’s life?

Why did emergency department visits involving misuse or abuse of prescription opioids increase 153% between 2004 and 2011? Why did emergency room visits related to alcohol increase 50% in the past decade?

Why are people going to the emergency room for substance use disorder, a treatable, chronic illness for which medical care should begin with a visit to one’s primary care physician, according to the Surgeon General’s report, released in November of last year?

Emergency rooms are filled with people who have opioid use disorders, alcohol use disorders, and other substance use disorders because we limit access to readily-available, evidence-based treatment. They shouldn’t be in the ER at all. They should have received treatment long before things went that far wrong.

What’s a citizen to do in a town, in a state, in a country that declares a medical emergency but won’t let its people have the medicine to treat the medical condition?

I’ve been asked to answer the question, “What can we do about the “opioid epidemic”? I share with you my opinions.

- Look around for elephants in every room. Even if you can’t see them, consider whether or not they might be there. If you see them, name them. Replace them with data.

- Demand definitions of terms. If politicians or policymakers use the term “opioid epidemic” or “opioid crisis,” ask “How do you define ‘epidemic’?” and “How do you define ‘crisis’?” Ask, “To which opioids are you referring?”

- Jettison these words from your vocabulary: addict, alcoholic, drug “abuse,” addictive personality, codependency, enabling, hit bottom, get clean, tough love. We are people who happen to have the medical condition of addiction. If you love us, help us. Period.

- Say nothing about addiction that you can’t support with data. If you believe something to be true, but don’t know if it’s true or not, either identify it as an opinion, or don’t say it. Personal opinions about cancer, diabetes or addiction, – all dangerous conditions that result in premature death – can kill.

- Demand data. Insist on sources. Don’t accept hype, opinion, belief, or personal experience as data.

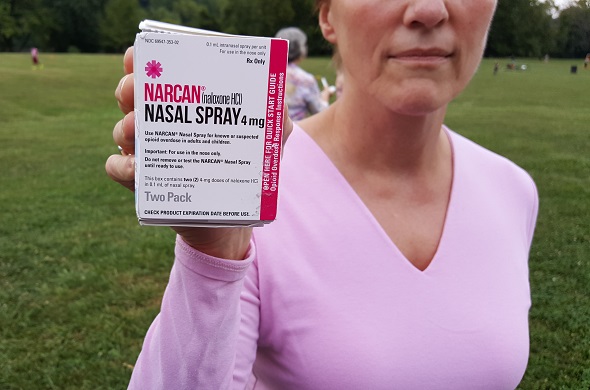

- Buy Narcan for yourself and your loved ones. It’s the opioid overdose reversal medication. I bought mine for $109 at CVS, University City Boulevard, in Blacksburg, Virginia. They currently keep one package on the shelf at all times and can have additional packages the next day, except on weekends. It’s sort of over-the-counter, but the pharmacist has to put a prescription label on it with your name? Anyway, I very much appreciate working with the CVS pharmacist at UCB and invite you to contact him.

- Contact every elected official you know and ask them why access to the only treatments known to cut the death rate for opioid use disorder by half – the medications buprenorphine and methadone – are restricted by federal law, state law, insurance company policy, and medical board policy. If we really have an “opioid epidemic” and an “opioid crisis” – a state of emergency in the Commonwealth of Virginia and the nation – ask them why the medications to treat opioid use disorder are nearly impossible to get. Insist they declare a true state of emergency and suspend all laws and policies that restrict patients with opioid use disorder from getting buprenorphine and methadone.

- Join with other stakeholders and put together an employment package – a work week limited to 40 hours, a position with a title, a house, a high salary, Virginia Tech football tickets, a brief contract, maybe 3 years – whatever it takes – and get some doctors in here who are willing to get certified to prescribe buprenorphine and treat people with opioid use disorder and other addictions full-time. Less than 10% of people with addiction get treatment and we have over 16,000 people with alcohol and drug problems in our area.

- Boost our local economy. Invest in treatment. Treatment is up to 7 times cheaper than incarceration.

- Whisper, then speak, into the silence. Maybe, maybe, 10 years later, it’s okay to ask people how they’re doing after the shootings. Ask yourself the same question. After community violence, 15% of people are expected to experience trauma symptoms. Of those, 5% are expected to develop substance use disorders.

- Ask people how they’re doing, period. Ask if there’s anything you can help with. Do that.

- Abstain for a month. You know that beverage or food or activity that gives you pleasure, that might be a tad problematic, but it’s optional? “Just say no.” Abstain without ceasing for 30 days. Note your observations and insights.

- Engage in personal reflection about your own beliefs about acceptable pleasure and acceptable pain. Talk about this with friends and family members, at books clubs, at places of work and worship. Engage in “clearspeak,” not “doublespeak,” not “addictionspeak.” State what you truly feel, think, believe, and know.

- Think less about what we can do to stop people from using alcohol and other drugs, more about how to help them, and a lot more about why in the world they would use them in the first place. Has America become a place where pleasure is hard to come by, pain is prevalent – especially when we are children – and substances work for both?

- Call me. If I can answer any questions, or be of service in any way, please call me. I offer tough talk in public, but I have no tough love to offer in person. Only love love. I will do what I can to help you.

Ut Prosim.

Thank you again for inviting me to speak.

Who has questions?

. . .

This post is part two of an expanded version of a talk on the opioid epidemic for the Montgomery County, Virginia Democratic Party on 8/17/17. Part one is here.

Photo by Mike Wade

Last updated 12/8/17

The opinions expressed are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the positions of my employers, co-workers, clients, family members or friends. This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.