When I feel something, I really feel it. When I think thoughts, they’re decorated. My sensitivity, intensity, and creativity are the primary traits that create a rich and wondrous life for me.

Sensitivity, intensity, and creativity are associated with the development of substance use disorder, not because the traits are liabilities in themselves, but lack of ability to regulate them is. Intense feelings that stay intense for a long time can be experienced as discomfort, even pain. Creative, untamed thoughts can generate alarming, worst case scenarios. If I didn’t get help, starting in infancy, with learning how to ease my highs and lift my lows, regardless of what I’m thinking or what’s happening, then normal, human life can cause me on-going distress. Shocks can leave me writhing. If I don’t have skills to help myself, substances, mercifully, help me.

Sensitivity, intensity, and creativity are associated with the development of substance use disorder, not because the traits are liabilities in themselves, but lack of ability to regulate them is. Intense feelings that stay intense for a long time can be experienced as discomfort, even pain. Creative, untamed thoughts can generate alarming, worst case scenarios. If I didn’t get help, starting in infancy, with learning how to ease my highs and lift my lows, regardless of what I’m thinking or what’s happening, then normal, human life can cause me on-going distress. Shocks can leave me writhing. If I don’t have skills to help myself, substances, mercifully, help me.

Maia Szalavitz introduced the metaphor of a “volume knob” to represent one’s inner experience in Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction. It’s a hugely useful way to convey the problems and problematic behaviors associated with emotional dysregulation, including trauma symptoms, and the power of emotional self-regulation to help create a sense of stability and well-being. Emotion dysregulation is predictive of addictive behaviors.

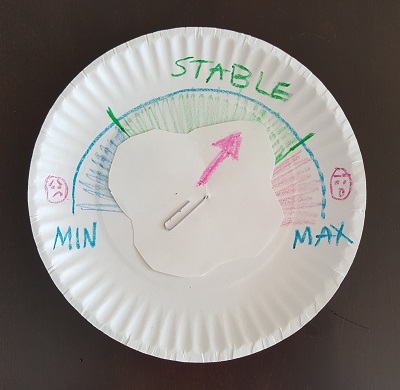

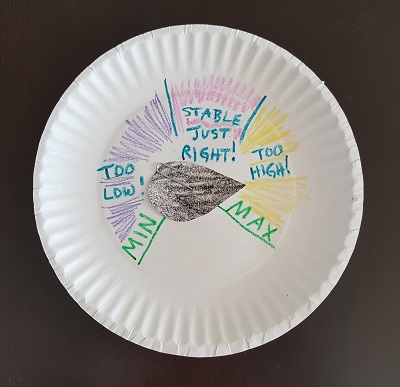

In my community, we imagine our inner emotional states, take two paper plates and a paper clip, do a little snipping and coloring, and create representations of our own inner volume control knobs.

First, each of us imagines a range of emotion that is individually stable for us. My range of stability, for example, is closer to “max” than “min.” I’m naturally curious and energetic, so I need a higher level of intensity to feel normal than others may. Another person with the same traits may feel more stable with a lower level of intensity that balances these traits. Each individual is unique and complex, and each case of substance use disorder is unique and complex. What will be meaningful to each individual will be one-of-a-kind.

First, each of us imagines a range of emotion that is individually stable for us. My range of stability, for example, is closer to “max” than “min.” I’m naturally curious and energetic, so I need a higher level of intensity to feel normal than others may. Another person with the same traits may feel more stable with a lower level of intensity that balances these traits. Each individual is unique and complex, and each case of substance use disorder is unique and complex. What will be meaningful to each individual will be one-of-a-kind.

After we envision a stable range of emotion for us, we use the large paper plate to serve as our scale, and we draw in our stable range at the top. Then we locate our own maximum and minimum points (by convention, max is clockwise but individuals are urged to depict what works for them), snip the other paper plate in a shape to serve as a pointer, then color as we wish. We poke a hole in the center of the “scale” plate, then poke a hole in the pointer, slip a large paperclip through both, and start adjusting our volumes!

Then we, together, practice the basics of emotion regulation. We walk through situations that create intense feelings for us, dial the pointer really high or really low in reaction, pause to identify and name the feelings, then talk through what might help shift the volume to a stable range. We use the best of our hearts and minds to help ourselves.

We then take turns offering each other surprise situations. This helps us practice pausing – even when caught off guard – to become aware of feelings. We don’t judge the feelings as good or bad, right or wrong, just name them and assess their magnitude. We don’t try to avoid or change our feelings, nor do we dwell on them, since these processes can actually intensify feelings. If our reactions or responses to the hypothetical situations keep us in a stable range, we keep going. If not, we pause, identify and name feelings, and start brainstorming ways that might shift the volume to a more stable range.

High highs and low lows are human. The birth of a child creates a normal high, and the death of a loved creates a normal low. But if I have substance use disorder, I can’t risk staying out of my stable range for too long. I can visit these places, but I need to live at home in a stable range.

Imagining a decorated inner volume control knob – whimsically and delightfully unique to me – helps me simply adjust the magnitude of my experience to a state that is helpful to me. My own traits strengthen me.

. . . . .

This exercise is an attempt to distill and apply the principles of emotion regulation derived by Marsha Linehan as a component of dialectical behavior therapy.

- Marsha Linehan, DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets, Second Edition, 2014

- Marsha Linehan, DBT Skills Training Manual, Second Edition, 2014

“People may not have caused all their own problems, but they have to solve them anyway.”

– Marsha Linehan

Emotion dysregulation is predictive of addictive behaviors.

This post is part of a series on evidence-informed, self-care for addiction. Self-care is NOT an evidence-based treatment for the medical condition of addiction. With evidence-based treatment scarce or denied, however, people with addiction must take treatment matters into their own hands.

The table of contents is here and posts are published in the category entitled Guide.

The views expressed are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the positions of my employers, co-workers, clients, family members or friends. This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.