A fundamental premise of cognitive theory-based counseling protocols is that, once people learn cognitive skills, they can take over as their own cognitive therapists.

What does this mean exactly?

A cognitive therapist uses the research-backed elements of cognitive theory to help a person acquire cognitive skills.

“Cognitive theories are characterized by their focus on the idea that how and what people think leads to the arousal of emotions and that certain thoughts and beliefs lead to disturbed emotions and behaviors and others lead to healthy emotions and adaptive behavior.”

– DiGiuseppe, et al., 2016

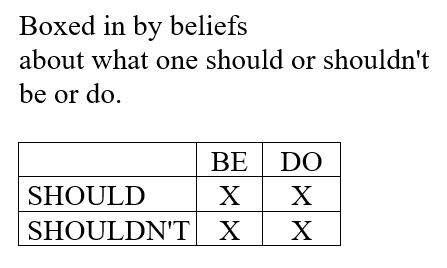

A person with cognitive skills, in the context of self-kindness, becomes aware of having felt, thought, spoken, or acted automatically, regains consciousness, deliberately frees themselves from getting boxed in by beliefs about what one should or shouldn’t be and do in favor of making principle-based decisions, sees reality as it is, and makes helpful, criteria-based choices about what to say or do next – or not say or not do.

“Take back your consciousness.”

At essence, a person with cognitive skills can become aware of when they need to say to themselves, “Take back your consciousness.”

People who seek counseling often realize that ways of feeling, thinking, speaking, acting, studying, working, and/or relating are interfering with their own intentions for themselves, and with their ability to relate effectively with themselves, partners, children, family members, instructors, co-workers, and/or community members.

Very often, these ways are unconscious and automatic, born of temperament, brain traits (such as sensory sensitivity or attention variations), childhood or later trauma, family of origin challenges, and learnings from families, communities, education, culture, nationhood, and the media.

Use of a set of research-informed counseling protocols – categorized as applied “cognitive theory” – can help people use awareness of their thoughts and feelings to identify these automatic ways, begin to see facts and realities as they are – however unwished-for they might be – assess probabilities, derive strategies, and make conscious choices based on their needs, wants, strengths, preferences, values, and priorities.

My work with clients is primarily informed by these cognitive theory-based counseling protocols: cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and cognitive processing therapy (CPT).

“Cognitive” can be considered a cold term, but cognitive-based counseling is anything but. The entirety of one’s feelings, thoughts, and experiences are courageously and deliberately honored and addressed. People map out what occurs, what’s in their hearts and on their minds, then use all that data to decide what would be the most realistic, helpful action to take. This meticulous examining is nothing short of heroic. Kindness, mercy, and bravery reign.

“Getting cognitive” also does not mean becoming robotic. One’s full humanity is seen, known, and appreciated. Reality is approached, not avoided. Reality is complex and dynamic; reality delivers unexpected shocks and sucker punches. Cognitive skills can’t undo what’s done, or make people “un-feel,” “un-think,” or “un-experience.” What they do is give people the power to help themselves through experience of all kinds, including hardships.

Self-kindness becomes direct rather than indirect. Rather than “giving oneself a break,” granting an indulgence, or engaging in a distraction, people can pause, use their attention, become deeply aware of what would be truly kind, and do that. With practice, self-kindness can feel moving, ecstatic, powerful, and peaceful, all at the same time.

Why become one’s own cognitive therapist and gain cognitive skills?

Even if only partial consciousness exists through ever-present stressors at home or work, immediately after shock or loss, after brutality or injury, or through congenital brain traits, accompanied by one’s consciousness, one can co-travel kindly and effectively with one’s experiences: inner and outer; past, present, future; kind or cruel; expected or unanticipated; desired or undesired.

In particular, a person can take back consciousness:

- from despair;

- from naturally and understandably feeling powerless, helpless, hopeless, victimized, overwhelmed, and in chaos by the facts of one’s existence: past traumas, past losses, the pandemic, memories, nightmares, symptoms, nearly automatic substance use, emotional and physical pain, and current incidents and situations;

- from replaying a past event in hopes of figuring out what might have made it go differently;

- from alarming and re-alarming one’s brain from replaying a past event;

- from taking troubling experiences in short-term/working memory into deeper, long-term memory through repetition (a “flashcard effect”);

- from attempting to anticipate, plan for, and script future events;

- after having developed an intense inner state to regain cognitive functioning;

- from learned actions intended to relieve intense inner states, such as use, overuse, or ill-use of substances – food, caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, prescribed and non-prescribed drugs – eating unintended foods and eating more than intended; purging; words and actions born of impulse, anger, and rage; many others.

- after involuntary occurrence of intrusive memories, thoughts, and nightmares;

- from attention going “there” instead of “here,” i.e. where it was intended to go and stay;

- from symptoms and traits of disorders such as trauma and stress disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit disorder, mood disorders, personality disorders, autism spectrum, and others.

Why take back one’s consciousness?

Outcomes. Simply put, people want to feel better and to do better. Based on decades of research, cognitive therapies help many people feel better and do better, much of the time, better than other therapies, and better than doing nothing.

Once one has one’s consciousness back, what does one do with it?

Co-travel. Co-travel with what is happening. Keep the self and one’s identity separate from one’s inner and/or outer experience. Operate from within one’s consciousness. State, for example, “I feel fear” rather than “I am afraid.”

Consider precise, person-centered language. Note the differences between “I am a person in remission from addiction” and “I am an addict.” Compare “I am a person who, at times, experiences anxiety” to “My anxiety is bothering me.”

How does one take back one’s consciousness?

Consider this sequence:

- Become aware of having a sense that something is a bit “off” and say to oneself, “Take back your consciousness.”

- Access the portion of one’s consciousness in which resides a) one’s inner wisdom and true self, b) awareness of this knowledge: one’s needs, wants, strengths, preferences, values, and priorities, and c) one’s cognitive skills.

- Engage self-kindness and banish belief-based self-judgment and self-criticism.

- Become aware of what one is feeling.

- Sort feelings into primary* and secondary** feelings.

- Kindly and humanely help oneself with primary feelings.

- Use secondary feelings as data about one’s thoughts. Ask, “What thought caused that feeling?”

- Identify thoughts as beliefs or facts.

- Shift one’s attention to thoughts about facts and reality.

- Comfort oneself if realities are painful or fervently wished otherwise.

- Using the criteria of one’s self-knowledge, values, and priorities for direction, imagine options, assess probabilities, then choose.

- Derive implementation strategies.

- Appreciate, acknowledge, and accept: “This is the best I can I think of with what I know at this time and with the resources I have.”

- Based on the above criteria, say or do – or don’t say and don’t do.

- Take back one’s consciousness again and again if any one of these occurs: second-guessing, self-criticism, self-judgment, repetitive thoughts (“noodling,” ruminating, listing), replaying past troubles, or anticipating future dire consequences.

Always, always practice self-kindness.

We are human, humans have extents and limits, reality is complex, and we each have such a short time on the planet to work things out. Kindness is merited.

. . . . .

*Primary feelings are natural feelings that go along with being human and happen automatically without thought: mad, sad, glad, afraid, surprised, disgusted, alarmed (includes fight-flight-freeze response).

**Secondary feelings happen as a result of thoughts – often thoughts that are opinions, beliefs, or rules – that cause feelings of shame, guilt, humiliation, self-blame, mistaken other-blame, regret, rage, dread, panic, despair, nostalgia, jealousy, righteousness, vengeance, and “ideations,” i.e. intrusive thoughts or fantasies of harm to self or others. Secondary feelings that result from thoughts cause suffering through 1) escalating natural feelings, 2) causing painful feelings, 3) creating a sense of “no escape,” which can result in feelings of rage, helplessness, and hopelessness, 4) increased reactivity vs. conscious choice, and 5) creating troubled interactions with others.

Photo images: iStock

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.