Telling people who they are, what they feel and think, or telling them what they have done or perceived isn’t real, right, or doesn’t matter is a form of psychological control and abuse commonly termed “gaslighting.” More extreme methods used to control captives and/or extricate information from them that attack the person’s selfhood and sense of reality – after first creating a bond, attachment, or dependence between captor and captive – are considered aspects of psychological torture.

The person with dementia may involuntarily gaslight the person who serves as the caregiver.

The person with dementia may involuntarily gaslight the person who serves as the caregiver.

(Using person-first language respects the personhood and individuality of all involved. For the sake of clarity and brevity, hereinafter, the person who offers care may be termed “caregiver” and the person who receives care is termed “person.” I define “caregiver” as a person who self-defines as a caregiver, either as a direct provider of care, a person who coordinates care, or a person who participates in care from a distance. Singular pronouns will be “they/their.”)

The person’s words and actions say, “I don’t know who you are, your every effort to communicate and connect with me is futile, and you can do nothing helpful for me. I reject your attempts to keep my behavior socially normative. You, your best efforts, your needs and wants, your mind, your heart – they have no power and are irrelevant to me. Our shared history is irrelevant to me. You, and who we are to each other, are now erased. You might as well not exist. Your perception of a reality in which you matter to me is wrong. You don’t matter to me.”

And the child may hear implied by the parent, the very source of their existence, a more global: You don’t matter.

“Gaslighting” effects from serving as a caregiver for a person with dementia can include attachment wounds and existential distress.

To limit “gaslighting” effects, a caregiver might:

Give due weight to the illness. In dementia, the brain’s deterioration causes involuntary symptoms in the form of troubling words and actions. The unknown and uneven directions and rates of deterioration may leave words and behaviors nearly random. Unresolved concerns from the past may, possibly, influence the person’s words and behaviors, but it may primarily be a malfunctioning brain, not the person, doing the speaking and acting.

Acknowledge the realities of the illness. Although we may desperately wish otherwise, no effective cure or treatment for dementia exists. Symptoms tend to persist and worsen in spite of any and all medicinal, behavioral, and environmental interventions.

Acknowledge the realities of witnessing the person’s words and actions. The human brain has evolved to work with reality very well, much of the time. Most people, most of the time, speak and act within a predictable range. Spoken and behavioral symptoms of dementia can seem alarming, surreal, and other-worldly. Feeling disoriented and distressed are normal responses to an abnormal situation.

Acknowledge inhumanity and humanity. Witnessing the inhumanity of another’s suffering and being helpless to do anything about it feels unbearable, but staying present and refusing to allow the person to suffer alone are acts of humanity.

Separate the self from what is happening. Survivors of hardships report the same wisdom: “I am here. What is happening is there. There are not the same. I am not what is happening. I am myself.”

. . . . .

In this post, I use the general term “dementia” to refer to specific neurocognitive disorders and other disorders involving deterioration of the brain. “Dementia” is a general term for a group of symptoms, not a disease in and of itself.

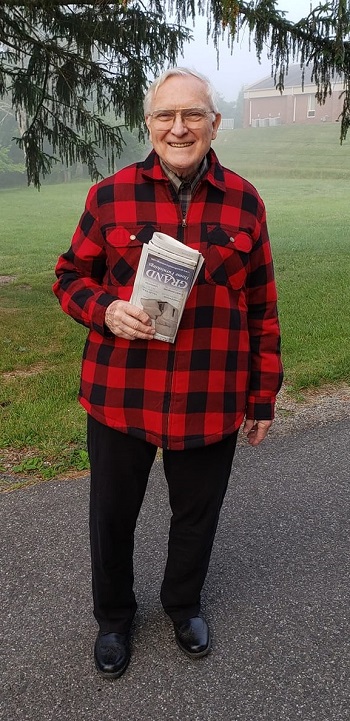

I serve as the primary care coordinator for my father, Robert “Bob” H. Giles, Jr., who developed symptoms of dementia at age 85. Before he lost his ability to reason and remember, he urged me to share any aspects of his story that might be helpful to others. I share with his permission and in his honor.

These are times of scarce mental health resources. Many have to serve as their own counselors. For assistance with existential distress, I have created this list of questions that may be helpful.

Serving as a caregiver for a person with dementia may, at times, feel traumatizing. These resources may also be of assistance.

- Self-Help Guide for Reducing Trauma Symptoms

- Addressing the Return of Trauma Symptoms

- Serving as One’s Own Cognitive Therapist

Other posts of possible interest

If you live in the Blacksburg, Virginia, U.S.A. area, provide care for a person with dementia, and are interested in forming a group, please contact me. I posted this request on 10/28/21 on the Everything Blacksburg page on Facebook.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.

Thank you so much for commenting, Roni. I have heard of Teepa Snow. Here is a link to the research literature she cites in support of her work. In my literature reviews of the research on caregivers for people with dementia, her work did not appear. If it does, I will definitely cite it. Thanks again!

https://teepasnow.com/resources/research-and-policy/

Hi, Anne, thanks for these resources. Unfortunately, I live in Montvale, too far to travel to join your group. However, may I suggest a resource for you if you are not already aware of her? There is a woman, Teepa Snow, who has done a slew of Youtube videos on all sorts of dementia topics. She is a wealth of information and help for those of us caring for loved ones with dementia. I also belong to a support group on Facebook for caregivers of dementia patients. It’s hit or miss, often new folks asking the same questions over and over, but also there is a lot of value in knowing we’re not alone, telling our stories to one another and asking for advice on specific situations. The group is https://www.facebook.com/groups/1516449868588963.