In early 2018, my father told me he had tried to vacuum the dining room rug but the machine wouldn’t turn on. He loaded the vacuum cleaner into the car and drove it to the repair shop. The technician plugged it in, flipped the switch, and the vacuum cleaner started humming. My father shook his head at the fickleness of machinery.

Several months later, my father told me he had driven his car to the gas station to fill it with gas but couldn’t remember how to use the pump. He asked his assistant for help. She drove with him to the gas station. She showed him again and again how to pump the gas. An action he had performed thousands of times for seventy years, he was unable to duplicate.

This is what I wish I had been told about dementia.

Your father has dementia.

Today, I understand why the “d-word” – “dementia” – is avoided by medical professionals, assisted living providers, and human beings everywhere. It’s not just out of fear. It’s out of terror. I understand that much about the cluster of symptoms known as “dementia” is unknown. Nonetheless, the suffering that resulted from ignorance for my father, me, and our family was cruelly unnecessary.

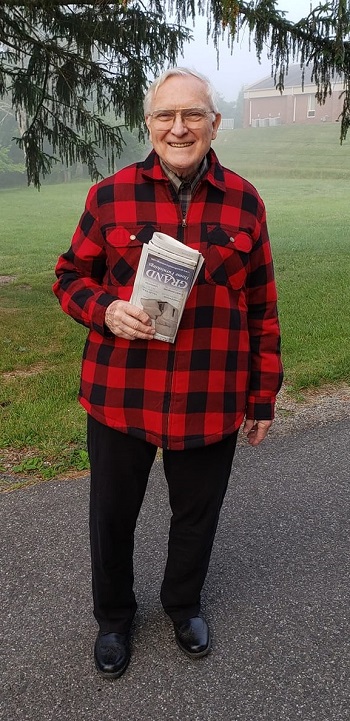

My father, an Eagle Scout, President of the Corps of Cadets as a senior at Virginia Tech, Professor Emeritus of his alma mater, having the ethics of a philosopher and the manners of a gentleman, was evicted from an assisted living facility after being there only five months because of his behavior.

This experience was appallingly cruel, humiliating, and baffling to my father, to me and my sister. In addition to traumatizing our family, I believe it was traumatizing for the staff members tasked with informing us of this decision as if my father had “gone bad.”

Instead, I imagine us receiving:

- a brief handout with the informational text from this post,

- the results of a board certified gerontologist’s assessment of my father’s state and prognosis, including an overview, in layperson’s terms, of the criteria by which the results had been determined,

- a list of options for alternative care,

- a supportive session to answer our questions.

I, my sister, and my father would have been informed. We could have made sad but calm arrangements for another place to live that offered the care he needed. Instead, the psyches of individuals in our family, our family system, and our family finances were detonated.

My father had moved out of his home of 50 years to a two-bedroom apartment. He was banished from it five months later. Under urgent conditions, we were able to find this Professor Emeritus one room in a small private residence.

I understand fear and avoidance. I protest inhumanity.

“A mind that could be so alive one moment with thought and feeling building toward the next step and then someone erases the blackboard. It’s all gone and I can’t even reconstruct what the topic was. It’s just gone. And I sit with the dark, the blank.”

– Sandra Bem, American psychologist, immediately after receiving a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, quoted in Jakhar et al., 2021

Dementia, resulting from one or more illnesses, is progressive and irreversible. There is no effective treatment or cure.

“Dementia” isn’t a diagnosis. “Dementia” is the term for a set of symptoms resulting from brain-damaging diseases such as Alzheimer’s and others. This damage to the brain results in reductions in memory, ability to recall and form words, ability to use logic and reason, and ability to learn new information. These symptoms are not a normal sign of aging. The causal disease is difficult to determine and usually requires an autopsy to accurately diagnose.

There is nothing that can be done.

Even if the world’s leading physicians provided medical care, a team of round-the-clock expert nurses provided daily living care, the most skilled occupational specialists provided stimulation and engagement, and the person was served gourmet meals with brain-focused nutrition at a spa, the person’s brain would deteriorate.

Dementia is progressive and irreversible. There is no treatment or cure.

Brain deterioration offers sucker punches of hope and despair.

For awhile, brain networks reroute to bypass damage caused by brain illnesses. As the damaged portions accumulate, brain networks can no longer bypass the extensive areas of damage. Intermittently, functionality may return due to unknown re-routings or temporary reconnections. Mental and physical functionality inevitably decline.

Ultimately, nothing works. Nothing.

Accept that “try harder” has no place in the world of dementia.

My greatest regret from caring for my father for the past three years is urging him to try harder. I encouraged him to focus. I broke procedures down into steps, typed them up, and put them under magnets on his refrigerator. I ordered books from Amazon with the subtitles “How to beat dementia.”

The person with dementia cannot try harder. The person can barely access the brain functions from which trying emerge. And trying has no impact upon brain deterioration.

For the person who is caring for the person with dementia, trying harder, trying to do more, trying other ways won’t help. I wish I had known to be merciful to my father and to myself and let go of trying harder.

You are very likely to experience existential distress.

The premise of “trying” is that one has the power to make a difference. Power, freedom, and efficacy are hallmarks of being human. Dementia challenges the very nature of being human, for both the person and the person’s caregivers.

In sum, per Freter, 2016, the person with dementia loses existential understanding on many levels: one’s own biography through loss of memory, loss of one’s ability to perceive or interpret reality meaningfully, imposition of new realities from delusion and hallucination, and loss of previously-derived strategies for making meaning of reality and one’s place in it. Neuro-degenerative losses result in the loss of an ability to make a new life story, to establish one’s existence as a self. The desire to be real in reality is deeply human. What’s termed “agitation” in dementia care may be the volatility that results from the human need to resolve perplexity and see and act on one’s deeply human longing to be real – to be self-determined – in the reality one perceives. Dementia makes this existential human drama perpetual.

The person with dementia is powerless over the deterioration of his/her/their brain. Many are conscious of the decline, suffer grievously, and experience profound existential distress.

Caregivers of people with dementia are powerless to stall or reverse the brain deterioration in their person, nor offer existential relief. As Jakhar et al., 2021 put it, “Dementia ravages what was known and loved about the person.” This results in caregiver distress on many levels. Not only does the caregiver experience sorrow at the decline of the person, but they helplessly witness another human strive fruitlessly and suffer.

My own existential distress has been deep and complex. I studied research on the particular existential distress of dementia caregivers and wrote these materials to help myself:

- Existential Concerns of People Who Care for People with Dementia

- Self-Help for Caregivers with Existential Distress (.pdf)

- A Self-Assessment and Tool for People Who Serve as Caregivers for People with Dementia

I am exploring the concept of “existential maturity” as possibly helpful.

Assisted death is not an option.

Assisted deaths are only allowed when the person is considered mentally competent to make the decision on their own. Even in states or nations that permit assisted death, the person’s decision has to be supported by physicians willing to document that support. Once symptoms of dementia have emerged, assisted death is no longer possible.

The unspoken “treatment plan” for people with dementia is ghastly.

Because people with dementia cannot receive physician-assisted suicide, this is the unspoken-of, barely acknowledged “care plan”:

- Keep the person as engaged and comfortable for as long as possible until they fall and/or develop another illness.

- Now bedridden, in pain, and feeling unwell, hopefully medicated for pain and distress, keep them as comfortable as possible.

- See how long their automatic eating and drinking reflexes work until they stop eating and drinking.

- Keep the person medicated and clean while they die from starvation and dehydration and/or a co-occurring illness or illnesses.

Plan for deterioration and death, not rehabilitation and restoration.

I am in the middle of this and have limited insight.

My father’s memory and reasoning began to decline in 2018 when he was 85. With great sorrow, he agreed to move into an assisted living facility. In February, 2019, he experienced psychosis, left the facility in the middle of the night, and was evicted.

My father experiences hallucinations and delusions. He continues to protect his daughters from as much hardship as he can, but he has reported he sees threatening men, dismembered animals, children to be protected, and substances to be scraped up painstakingly from the floor. He once gestured with his cupped hand and poured the substance into my hand as if it were glitter.

When he left the facility that evicted him, he stated that he heard people in the next room who were planning to kill him. He headed out in the snow to walk to his male friend and assistant’s house, about two miles away.

Subsequently, I learned that eviction of elderly adults from assisted living facilities is common.

My father stayed with me for several nights until we learned of an opening at a three-bed, private, assisted living residence. His emotional, mental, cognitive, and physical functioning decline incrementally. In Orwellian terms, “Falls are part of the process.” He fell on 09/23/21 and experienced a blow to the chest that caused him great pain. As of this writing, 12/27/21, he has regained physical comfort and stability.

My father has lived at a home that is not his own, with people he does not know, without the ability to read the research in his field or contribute to it, intermittently plagued by perceptions of threat and horror, for two years and nine months. If he lives, that will be three years in February, 2022. If he lives, he will be 89 years old in May, 2022.

Note to the reader: Do you see how I am not answering the question, how I am writing about what happened rather than what I feel or think? This is shock and numbing, understandable and normal under these circumstances. I am kind to myself and accept that, until my father no longer suffers, I will suffer to some extent.

Grieve now.

Paradoxically, this is, of course, difficult to do during shock and stress. So, why? Isn’t it better to control emotions and keep it together?

Although it’s more complicated than this, the human brain has actually evolved to handle both the joys and sorrows of the human condition. Put more simply, humans have evolved to naturally feel natural emotions. Resisting and avoiding feelings taxes the brain’s functions and resources more than experiencing them does.

The problem is that some thoughts exacerbate feelings. Thinking “Things shouldn’t be this way” escalates feelings to beyond-capacity levels.

I wish I had been told this: “Try not to tell yourself you should feel differently, should be doing better, or should be doing more. Cry and cry about the truth of what is, what can’t be done and changed, and how hard it all is.”

O, the synonyms for “grief”! What am I feeling?! Sadness, sorrow, bereavement?! How do I help myself with this?! I did research and wrote about grief, too.

Experiencing grief while caring for a person with dementia is complicated by anticipatory grief – grieving now at the slow death of the person’s selfhood, all the while knowing you will grieve again at the loss of the life – disenfranchised grief from private losses others may not understand, and ambiguous grief – both wanting the person to die and free themselves and you – and wanting to hold onto them forever.

It’s complex.

Advocate for research-informed relief from suffering.

Many beliefs exist about how to care for people with dementia. Humans naturally practice folk medicine. Meaning still matters. Use PubMed to research conditions troubling your person, derive practical solutions, and ask for their implementation.

Know that caring for people with dementia requires skills that love for them doesn’t provide or teach.

How to engage with, lead, lift, and bathe people with dementia so they don’t suffer from unintentional consequences of unskilled care, e.g. sores and urinary tract infections, requires skilled care. Love does not equip people to provide skilled health care.

Long ago, my father asked and answered his own set of existential questions. He took both me and my sister to the attorney’s office and gave us complete, joint control of his affairs. He insisted that, if he became unwell, neither I nor my sister would bring him to live with us. He wanted us to be free to live our lives.

I see now that I would likely cause greater suffering to my father if I were to equip my guest room for him. He needs 24-7 assistance. I would do my best to schedule around-the-clock care for him. If the skilled caregiver were ill? My unskilled, untrained love would be on duty.

Speak your love now.

Although intermittent functionality may occur, speak of your love now and perform your loving acts now during this time while some mutual connection exists. The connection waxes and wanes. Eventually, the caregiver may receive little but the knowledge that they are keeping this struggling, suffering person from having to endure this troubling illness alone.

Watch for, alleviate, and get help with trauma symptoms.

I predict that few caregivers of people with dementia can avoid developing symptoms of exposure to trauma. Hearing, seeing, witnessing, and experiencing distress over and over again, over time, is deeply wearing on people. Here’s a self-help guide for reducing trauma symptoms.

Be cautious about asking for help.

I prefer to think most people mean well. However, when I have expressed distress or had difficulty with a problem, I have generally been told that I am not feeling or thinking correctly, or am perceiving things incorrectly. In clinical terms, this is termed invalidation.

Serving as a caregiver for a person with dementia is almost unbearable. The added burden of “help” from others has almost broken me. I have learned to consult a small group of safe people who are not afraid of my – or their own – feelings, thoughts, and experiences.

My greatest source of comfort has been the published research on dementia and on serving as a dementia caregiver. Accompanied by facts and reality as best as the finest minds using rigorous scientific methods can discern, my plans are reality-based and, therefore, are more likely to be effective than myth-based or belief-based speculations.

Be your own care provider.

No matter how large or small a caregiver’s group of supporters is, most of the time, caregivers serve solo as their own 24-7 support staff members, consultants, mentors, and solace.

Practice a particular kind of self-care. From self-care protocols, make and execute a plan to engage in self-care practices that foster the qualities needed by dementia caregivers: forbearance, endurance, and resilience.

- Self-Care Checklist

- Existential Concerns of People Who Care for People with Dementia

- Self-Help for Caregivers with Existential Distress (.pdf)

- A Self-Assessment and Tool for People Who Serve as Caregivers for People with Dementia

- Self-Help Guide for Reducing Trauma Symptoms

- Becoming One’s Own Cognitive Therapist

- Dementia Caregiver category on this site

See, and pause to acknowledge, small beauties.

I have dismissed advice like this in the past as invalidating, toxic positivity.

However, dementia robs life of so much that small moments of beauty feel like satiation of hunger. I savor them like wedges of baklava dripping honey down my arm.

How I miss sharing such things with my father! How I miss my father!

I offer a paraphrase of Irvin Yalom, M.D., who, at 88, after losing his wife of 65 years and finding himself living alone during a pandemic wrote: “Even if the small things that happen are known only to me and can’t be shared with others, they are still beautiful and still matter.”

Knowledge is power.

A friend confided in me that dementia was feared to have developed in a loved one. I expressed regret and sorrow and mentioned one or two items on the above list. The person grabbed my arm and said, “You’re not cheering me up!”

I have pondered this observation and she is completely right. I don’t have cheer to offer. But I do have power to offer.

Before the first episode of psychosis hit, my father said, “If you think anything about my story might be helpful to others, please share it. You have my permission to share it.”

Silence about dementia keeps its realities unknown and capable of enormous damage. If I had known three years ago what I know now – readily available information! – I could have more skillfully stewarded my father, myself, and our family through this time of beyond-words hardship.

With his permission, I share his and our story in case it may prevent others from the needless suffering brought about by simply not knowing better.

. . . . .

Other than Alzheimers New Zealand, Alzheimer’s Society – United Kingdom, and Alzheimer Society of Canada, I have no other general sites, books, or resources to suggest. I have been referred to other sites of organizations and pundits. I found pat answers. I have not found the pundits’ names among the published research literature, nor citation of sources among their posts. Folk wisdom, practice wisdom, quackery, and generalizations from case studies dominate contemporary commentary on dementia.

I found this 6-hour continuing education course for counselors, Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias Certificate Program, extremely informative.

I found these books on dying troubling, but they helped give me power. The list is in alphabetical order by the author’s last name.

- Butler, Katy. The Art of Dying Well: A Practical Guide to a Good End of Life, 2019

- Gawande, Atul. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, 2014

- Klune, TJ. Under the Whispering Door: A Novel, 2021

- Yalom, Irvin. Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death, 2008

- Yalom, Irvin and Marilyn Yalom. A Matter of Death and Life, 2021

Added 2/8/22

I found the “Care for the caregiver” section in this guide from Harvard Medical School of value. It was published in 2018. A copy was given to me by a colleague in February, 2022.

This guide may be the one that care facilities need to give to the families of their residents:

Update on 4/20/22

Based on my father’s experience of anguish, I have written my own Advance Directive for Dementia Care.

The views are my own. This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.

Mom had early-onset Alzheimers with symptoms beginning at 52. After 20 years she finally was free. What you have written through your grief is a priceless treasure to others. Thank you!

Annette, I am so very sorry for your own hardships. Thank you so much for sharing such a heartening and affirming message.