No one really knows what addiction is. Brain imaging studies help researchers get closer to understanding brain structures and functions involved with what is experienced on the individual level as wanting to slow down, switch, or stop, and not being able to. We may never know exactly what goes on in a brain’s 86 billion neurons and perhaps a similar number of glial cells. In this context, differentiating between cause and effect – this thing caused that thing – and correlation – these things happened at the same time but are unrelated – is difficult.

Not knowing what causes problems makes them difficult to solve. With substance use problems, many beliefs, opinions, and theories underlie treatment protocols. What is meant by “treatment” and “cure”? Harm reductionists advocate for what’s termed “safer” use on the individual level, which may range from abstinence to supervised injection. The criminal justice system, child protective services, medication programs, insurers, and many employers and family members may mandate proof of abstinence via urine drug screen, whether or not that’s medically or therapeutically sound. Individuals may seek to abstain for their own reasons.

But estimates of rates of return to use with most methods range from 60% to 80%. Then there’s the confounding factor of what’s termed “spontaneous recovery.” A significant number of people “age out” of addiction without treatment. Why are some people able to moderate or eliminate use on their own, while some cannot? And why is “recovery” so variously defined and so variously achieved?

In such swirling uncertainty, I find Steven Covey’s guidance reassuring and clarifying: “Begin with the end in mind.”

What can we do together to increase the likelihood of achieving the end in mind?

If you are considering counseling, or have been mandated to counseling by authorities, we’ll assume that abstinence from banned, illegal, or non-prescribed substances is your objective, or that lessened use, within a range tolerated by authorities, is your end in mind.

The purpose of research is to use the wondrous logic and treasure of human minds to design and implement experiments whose results suggest what would be helpful to most people, most of the time, better than other things, and better than nothing.

Research is clear on what can help people limit substance use. However we define addiction, whatever mechanisms are at work in the human brain, whatever neurobiological, developmental, social, environmental, or historical forces are at play, people can learn and implement specific skills that may result in decreased substance use.

I am working on a book manuscript with a co-author to describe this process for those who prefer a self-help guide. In the meantime, I post resources and excerpts on this site, and offer individual and group counseling for those who prefer interactive learning and support.

Briefly, what research suggests helps people limit substance use begins with medical care. Specific medications are available to assist with some specific substance problems (alternately termed substance misuse, substance use disorder, and addiction). For example, the media is currently interested in opioid use disorder, for which the medications buprenorphine and methadone are the first-order standard of care. In some cases, medication is sufficient to help people meet their goals; counseling may not be necessary. Since stress is correlated with increased use, or recurrence of use, and untreated physical and mental conditions cause stress, individuals need medical care for whatever ails them, even if it’s an itchy rash or trouble sleeping. What medical care can ease needs to be eased.

In the context of receiving on-going medical care, individuals can then mobilize their strengths to help them do more of what they intend to do, or what they are required to do.

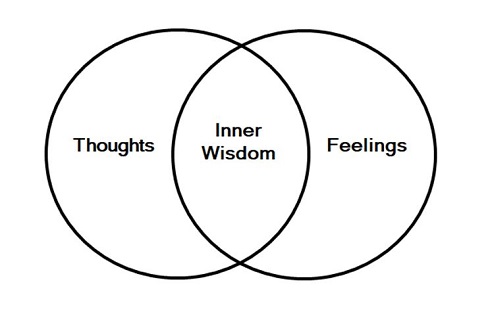

On their own, or with the aid of a counselor, individuals can begin to learn, and to implement, techniques that help them with what’s at the heart of many mental and emotional challenges: insufficient skill with emotion regulation. In a nutshell, this involves becoming aware of to what one is giving one’s attention and deliberately deciding whether or not to continue or discontinue that focus; identifying feelings and thoughts; adjusting the inner “volume” on one’s feelings; sorting one’s thoughts into “helpful” or “unhelpful” categories, then shifting attention to the “helpful” ones; and becoming aware of physical sensations and reducing discomfort.

Research suggests that these straightforward techniques – what I term “awareness skills” – acquired with deliberate practice and implemented consciously, offer remarkable strength in managing the emotional states and thinking patterns that, if left untended – while they may not cause recurrence of use – are correlated with a return to use.

Except with some medications for some substance use disorders, we don’t know how to directly treat the brain for addiction. While some methods are posited to directly ameliorate problems in the brain, the pace will be too slow for most people who want or need to reduce use now.

As they begin to use awareness skills, individuals can explore concerns related to substance use, including environmental cues and social capital. While people with addiction can often will themselves to choose to postpone use, compulsive use is the primary symptom of the illness. (This is another reason why medications for specific substance use disorders are invaluable. The lack of medication for methamphetamine use plagues many with amphetamine use disorder who attempt to cut back or abstain.) The brain alterations caused by addiction interfere with what we term “will” and “choice.” What strategies does one use in a double bind game of needing a function to address an illness that can compromise that very function?

Whether termed craving or longing, absence of the substance creates an intolerable state akin to pain for many people with addiction. Learning and using emotion regulation skills under such pressure, at the same time trying to discover and engage with replacements for the purposes served by substances, all the while continuing to interact effectively with one’s partner and children, and to hold down a job – well, it’s all very difficult.

And most people with substance use issues have experienced trauma, particularly in childhood. Over half have been diagnosed with mental health issues. Many have physical pain. When substance use ameliorates these conditions, in the absence of substances, symptoms can escalate to unbearable levels.

Where can we turn for help with this Gordian knot? The research on addiction is actually quite clear on what is helpful. Comprehensive reports on addiction research were released in 2016, first by neuroscience journalist Maia Szalavitz, and then by the U.S. Surgeon General. Evidence-based treatment is at hand.

And no wonder research suggests that, coupled with medical care, skills-focused therapies – rather than personal analysis – can be helpful to people with substance issues who want to reduce or eliminate use. If I have substance use issues, personal insights might be helpful, but only if they free me to take action. I need something to do right now. Addiction is defined as a brain disorder. Addiction is not a problem with the self.

Research reports that these therapeutic modalities can be helpful to people with trauma, mental health issues, and/or substance use issues: cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and its varieties, including Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), Motivational Interviewing (MI), contingency management (CM), and mindfulness-informed therapies, all offered in the context of, as Maia Szalavitz puts it, “Love, evidence & respect.”

Individuals can study these methods on their own, or work with a counselor, individually and in groups, to use these approaches to address their concerns. A primary skill to acquire is distress tolerance to endure the opposites that are true for many people with addiction: “I want to use AND I don’t want to use.”

Simply put, in tandem with medical care, if I have a substance use issue, if I’m aware of what’s going on in and around me, and have some skills to take action on what might be helpful to me, some supportive people in my life, and adequate resources, I may be able to gently – or muscularly if need be – help myself use substances with less risk, perhaps not at all.

Denigrating, devaluing, and dehumanizing through confrontation, humiliation, and incarceration do not reduce substance use, whether inflicted by others, or through one’s own thoughts. Some beliefs we hold about addiction are simply wrong.

Discussions about addiction treatment and policy seethe with controversy, debate, and acrimony – a lot of emotion dysregulation! I try to slide those aside like dusty curtains to see what’s possible out the window.

To achieve the end in mind – to reduce or end substance use, either by preference or mandate – in my work with myself and others, I have found kindness to be the most helpful modality. Self-kindness and other-kindness. Next would be acknowledging reality without shame or judgment.

If I am working with you, or will in the future, it is my honor, privilege, and delight.

. . . . .

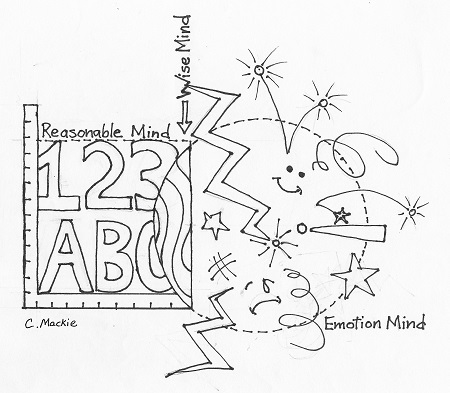

Coloring page interpretation of DBT’ “States of Mind” by Christy Mackie. Downloadable .pdf coloring page opens in a new tab here.

The views expressed are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the positions of my employers, co-workers, clients, family members or friends. This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.