What can you do to help the over 16,000 people in the New River Valley of Virginia with substance use disorders? Here’s an executive brief.

Executive summary:

- Do no harm.

- Help people get health insurance and medical care.

- If they’re open to it, accompany people to their appointments.

- Start a SMART Recovery meeting.

- Lobby against federal and state restrictions on medications that treat addiction.

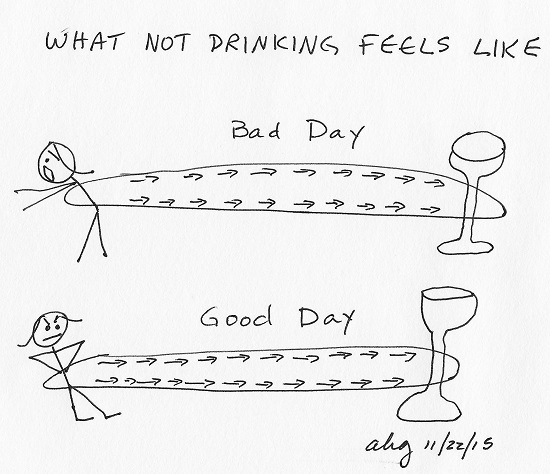

- Host substance-free gatherings and events, both at home and in the community.

- Help people help themselves.

- Inform yourself about addiction and addiction treatment in our locale.

An explanation of #1 – Do no harm – follows. The full brief is here.

1) Do no harm.

What harms people with substance use disorders?

- Telling them that your personal experience with addiction, or your knowledge of several people’s experiences, will work for them. Addiction treatment needs to be research-backed, evidence-based, recommended by health care professionals, and individualized for each person’s unique case.

- Telling someone they have to “hit bottom” before they recover. “Hitting bottom” is a state of physical and mental emergency that can result in death.

- Telling someone to “Just stop” and “Get over it.” That’s like telling someone with Parkinson’s to stop shaking or someone with dementia to “Just remember!” Addiction is a brain disorder. Like people with Parkinson’s, dementia and other chronic brain disorders, people with addiction need medical care.

- Telling someone your belief or opinion about addiction. If you can’t cite the research on what you’re saying about addiction, don’t say it.

Most of the over 16,000 people with substance use disorders (SUDs) in our area struggle with alcohol, not opioids. Most people with opioid use disorders struggle with use of other substances as well – including alcohol. Most are not receiving care.

“Do not attempt to take away a person’s main means of trying to cope with pain and suffering until you have another effective coping strategy in place.”

– Alan Marlatt

What limits people with substance use disorders from receiving evidence-based care in our locale?

- Continued belief – by lawmakers, health care professionals, treatment professionals, and society at large – despite the vast and extensive data that reports otherwise – that addiction is a moral problem, not a medical one. Addiction is believed to be the individual’s fault and the individual’s responsibility to cure. Lack of improvement is blamed on lack of character and effort.

- Federal and state restrictions on access to addiction medications.

- Lack of knowledge among health care providers and treatment professionals on research-backed, evidence-based treatment for addiction, including medications for addiction. Most people with substance use disorders get recommendations in the reverse order from the standard of care: support group attendance, then, if that doesn’t work – which the evidence says it won’t for most people – counseling. Rarely is the first-order, standard of care – medication – considered.

- Lack of sufficient trickle-down knowledge to society at large about the latest research on addiction. People still believe they know best, even if the data says otherwise.

- Lack of early treatment. Many people in our locale have acute, advanced cases of addiction from long-term, multi-year lack of evidence-based treatment or from mistreatment. The signature brain impairments of addiction result in behavioral symptoms that can make people with SUDs challenging patients. As with acute, chronic cases of other life-threatening illnesses, premature death may result. Harm reduction or palliative care – not incarceration or multiple rehab stays – may be the most humane and cost-effective option for our citizens with the direst cases.

- Arguments about what prevents addiction. The only thing that prevents addiction is never having done the thing – no sip of beer snuck from a parent’s beer can, no first cigarette, no first toke, no sex, no porn, no Internet, no gambling, no exciting experimentation of any kind. The vast majority of Americans, about 86%, do not develop addiction. Through a complex set of known and unknown factors, 14% do. Attempting to prevent addiction through limiting supply is attempting to prevent people from being human. It has, and will, fail.

An explanation of #1 – Do no harm – is above. The full brief is here.

The opinions expressed are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the positions of my employers, co-workers, clients, family members or friends. This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.