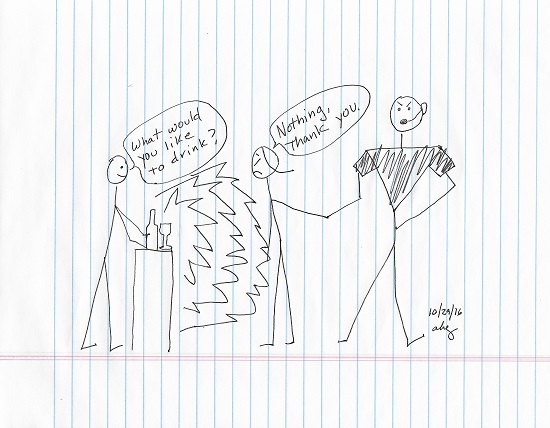

I quarantined myself from friends’ homes, restaurants, public festivals, business networking events, anywhere alcohol was seen or served. After nearly 4 years of abstinence from alcohol, I began to realize that I had had drinks with nearly every person I saw and in nearly every place I went in my small town. My entire world triggered me. I became increasingly relegated to solitary confinement.

I am a person with alcohol use disorder with the very human need and longing to be with people. A holiday afternoon, alcohol-free party at a place I had rarely frequented seemed safe. The usual descriptive paper tents describing the food were missing, but I enjoyed the luscious main dishes and the conversation with my table companions. I had carefully saved room for the steaming bread pudding on the back table. In front of the serving dish were two bowls of sauce. I’m right-handed so I ladled on sauce from the right-hand bowl. I sat down, took a small spoonful of pudding and sauce, then took another one. I felt the burn on my tongue and that shimmer in my mouth and that rise of heat into my nasal passages.

I am a person with alcohol use disorder with the very human need and longing to be with people. A holiday afternoon, alcohol-free party at a place I had rarely frequented seemed safe. The usual descriptive paper tents describing the food were missing, but I enjoyed the luscious main dishes and the conversation with my table companions. I had carefully saved room for the steaming bread pudding on the back table. In front of the serving dish were two bowls of sauce. I’m right-handed so I ladled on sauce from the right-hand bowl. I sat down, took a small spoonful of pudding and sauce, then took another one. I felt the burn on my tongue and that shimmer in my mouth and that rise of heat into my nasal passages.

After nearly four years of fleeing it, alcohol had caught me.

. . . . .

The trouble with alcohol for me is that once I start, I can’t stop. I can’t stop drinking too much at one sitting, even though I set a personal limit, and I can’t stop drinking day after day, even when I commit to not drinking that day or the next. Drinking a lot of alcohol day after day is hard on the brain and the body but if I wanted to continue doing that, I would support my personal freedom and choice to do so – with one huge exception. If I say or do mean or dangerous things when I’m with you or others while I’m drinking, well, I’ve violated your right to be safe in my company.

Addiction is defined as persistence despite negative consequences. My drinking provided me great pleasure, great relief, and inexpressible benefits, small and large. In old school terms, I neither “abused” alcohol nor, in the new Surgeon General’s lingo, did I “misuse” it. We all know what alcohol’s purpose is and I used it intentionally for just that. But my drinking also resulted in negative consequences for others. Scaring people when I fell down staircases was one negative consequence I have shared publicly. I had to stop.

. . . . .

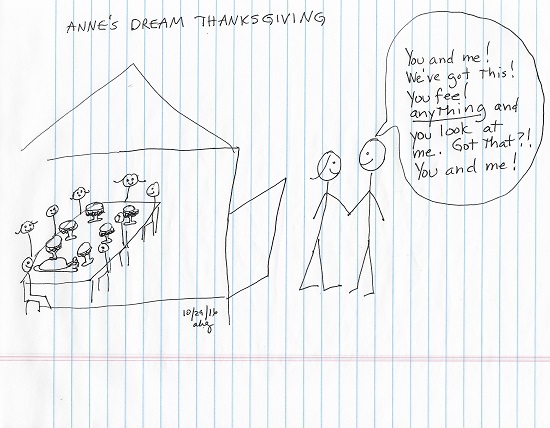

Nearly instantly, when I felt the alcohol in the bread pudding sauce take over my senses, an image of a lighted Christmas tree came to me, my father seated beside it wearing a shirt, tie and sweater vest and letting me, his little girl, have a sip of his holiday drink. My father smiled in a circle of green and red and blue Christmas tree lights lights. Oh, another taste of bread pudding would mean a bit more time with that treasured memory!

I looked up at the lady across the table from me and said, “This has alcohol in it.” I felt tears come into my eyes. The lady seemed confused, but looked at me kindly.

I stopped eating. I stood up. I walked across the room to the waitress and asked her to please take my plate away from my seat. I told her I couldn’t have alcohol. I filled a coffee cup with decaf. The waitress returned. She said, “Our bad. We usually have labels. The sauce on the right has bourbon. The one on the left doesn’t. So you could have the one on the left.”

I was able to stay a few more minutes, even to taste the plain sauce, very plain if I recall correctly. But shock was passing and panic starting. Once I start, I can’t stop. Was this the beginning of my end?

In the parking lot, four years of experience with what the Surgeon General terms recovery support services, or RSS, kicked in. I knew I needed to call someone with tough, long-term abstinence for help. As well-meaning as the lady across from me was, she had no idea – as I had no idea before I developed it myself – of the ghastly rip in selfhood made by addiction to a substance. I needed to survive it so I needed to talk to someone who had.

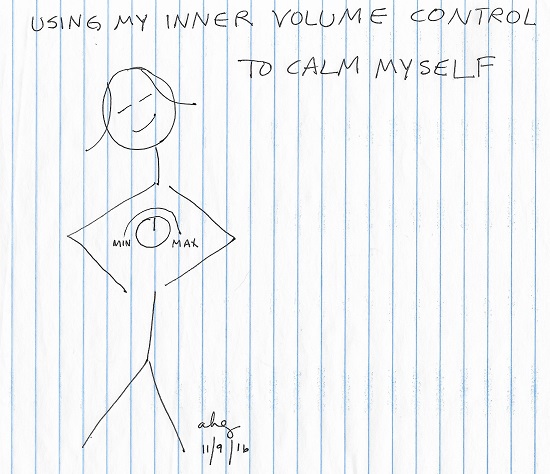

The first person I called didn’t answer. The second person I called didn’t answer. I got in my car and tried to think. But neuroscience tells us what common sense does, too: emotionality and rationality can be inversely proportional. The more upset I get, the less I can think.

I felt bushwacked by the involuntary return of alcohol to my system. I felt tricked into relapse, defeated by my mightiest foe.

And then my phone rang. It was the first person returning my call. I was relieved but not surprised. When people who have what I have call each other, we know it’s urgent. We do our very best to call back.

Apparently, involuntary consumption of alcohol happens often. Alcohol is so pervasive that any food or beverage we didn’t make ourselves is suspect. Alcohol shows up in innocent-looking soft drinks and lemonade, poured into desserts and sauces. We’re advised to just spit it out and keep going.

“You’re all right,” the person said.

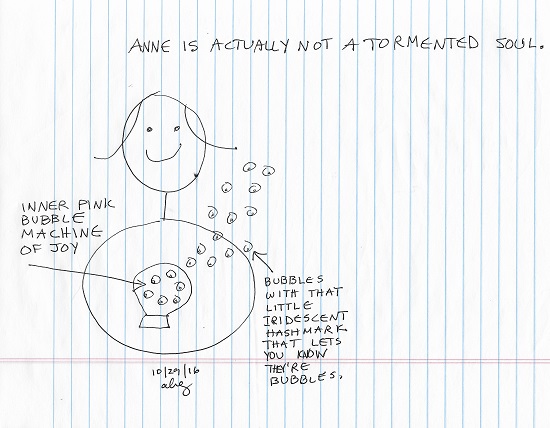

As the hours, then days have passed, and I have continued to be abstinent from alcohol, I have felt increasingly exultant. Alcohol has not made me return to it. I am not its captive, its slave, its gimp. I am not alcohol’s helpless, hopeless, powerless victim.

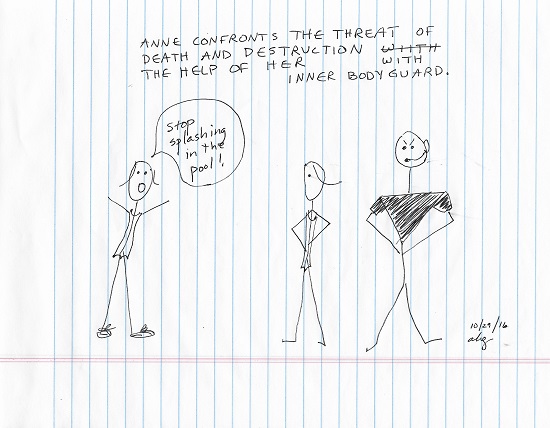

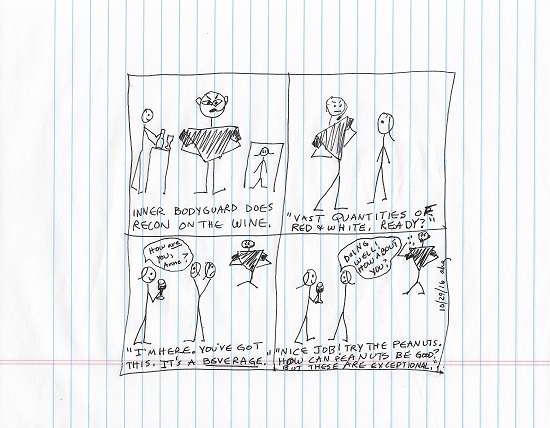

The next night, I attended a gathering at a restaurant. I invited someone who is abstinent to accompany me. Half sat at the bar and half sat at the table. I sat at the table. I may have some control over my use of alcohol, but I am not a fool. My newest RSS pal, the Surgeon General, says most people with alcohol use disorder aren’t in remission until 4 to 5 years of abstinence. With 3 and 11/12 years of abstinence, I accept 1 and 1/12 years more of constant vigilance to go.

While I was seated at the restaurant table, a woman stopped by to chat and stood with her glass of red wine right in my face. Involuntarily, I leaned towards her glass. Bourbon wasn’t my drink. Wine was.

Most of the past four years, I would have been sobbing in anguish as I wrote that. Today, I’m laughing. A near relapse one day, and the next day I’m sniffing someone else’s beverage? What a ridiculous disorder this is.

And then gravity returns. Addiction is despicable to the people who have it and to those who love them. And, for many, deadly.

This southern lady didn’t spit out her bourbon-laced bread pudding this time, but she will next time, albeit behind a napkin. I thought I had all the needed prepositions on the to-not list – don’t be “with,” “by,” or “around” alcohol. I will now watch out for alcohol getting “in” me – against my will, against my wishes.

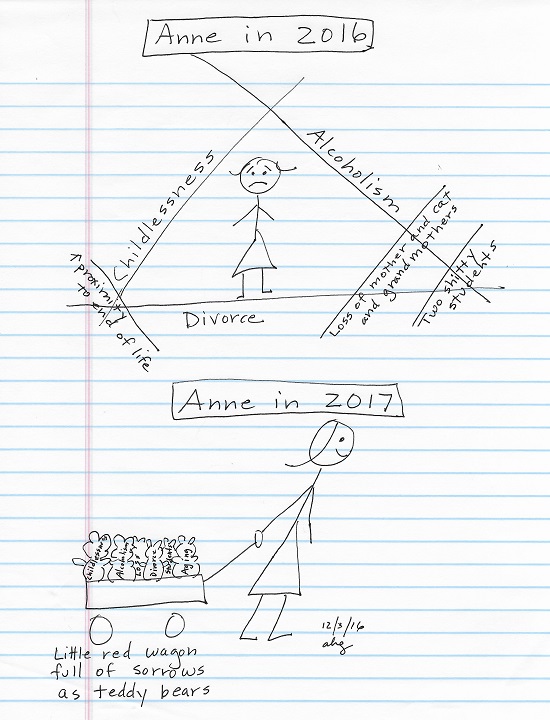

I have felt bent double, waiting, wearing terror like layers of dark coats, trying to cushion myself from the wicked, arbitrary decision of alcoholism to drop its boot on me again. It dropped. With whatever shreds of self left after everything that’s gone down, I pushed myself out from under it. I stood up.

I feel free in a way I haven’t in nearly 4 years. For me – and my anecdotal experience cannot be generalized to others – a small amount of alcohol, involuntarily consumed, did not result in an involuntary return to active use. The next day, after I leaned into the wine, I felt a novel indifference. The disorder made made me lean in. But I had power over what I did next.

If I were sitting at a restaurant all by myself and the maître d’ sent me a complimentary glass of wine, perhaps chilled cabernet sauvignon, nose-tickling champagne, or merlot just cooler than room temperature, ooh, how I would ache to drink it! Days ago, I might have.

Not today. My little involuntary relapse took the edge off the mystery. Yep, that’s what alcohol tastes like. Yep, if I had more, as the Surgeon General reports on page 2-20, I’d feel that fantastic first “euphoria as well as the sedating, motor impairing, and anxiety reducing effects of alcohol intoxication.” Woo-hoo! Who cares about motorly impairment when I’m feeling this awesome?!

Yep, if I had a little more, I’d want a lot more. For days on end.

Nope, not today.

Today, as the person who has what I have assured me, I am fine.

In fact, I’m feeling the best I’ve felt in nearly four years.

Photo of me taken by a table companion during tea at Smithfield Plantation on 12/5/16, the day before my “relapse.”