I estimate it took me between 15 and 20 hours over 10 days to read Maia Szalavitz’s new book, Unbroken Brain. I read every word of its 288 pages, 33 pages of notes, and 14 pages of index subjects.

A few pages in, as I wrote for The Fix, “When I read these words in Maia Szalavitz’s Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction: ‘I felt utterly stripped of safety and love. And so, what tormented me most as I shook through August of 1988 wasn’t the nausea and chills but the recurring fear that I’d never have lasting comfort or joy again,’ I stopped reading, put my face in my hands, and cried. I wasn’t alone anymore.”

A few more pages in, I posted on my personal Facebook page, “I am experiencing cognitive dissonance,” and linked to the term’s definition on Wikipedia: “In psychology, cognitive dissonance is the mental stress or discomfort experienced by an individual who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values at the same time, performs an action that is contradictory to one or more beliefs, ideas, or values, or is confronted by new information that conflicts with existing beliefs, ideas, or values.”

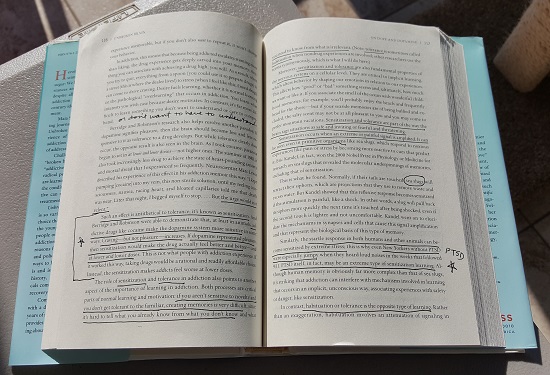

Unbroken Brain came out on April 5, 2016. I wish I could remember the exact search phrase I used to discover the book on Amazon, but on April 13, I typed in something like “how to save myself from addiction with long-term sobriety.” Once I read the book’s description, “[O]ur understanding of addiction is trapped in unfounded 20th century ideas, addiction as a crime or as a brain disease, and in equally outdated treatment,” I downloaded the book for my Kindle and began reading immediately. Finding myself desperate to underline passages desperately important to me, I ordered a hardback copy which arrived April 26.

Why have I included dates? I have probed and probed for more erudite phrasing, some way to step back from this personal, personalized statement. About reading a book. One book. In 10 days. But I truly can compose no lesser or greater sentence: I have a pre-Maia and post-Maia life.

I tried very, very hard to have “good sobriety” once I became abstinent from alcohol. I tried to feel “happy, joyous, and free.” I did everything I could to help myself. But those first 3 1/3 years of abstinence were spent primarily in pain.

At essence, I hated myself for what I had done to myself by becoming addicted to alcohol. I hated myself for bringing upon myself the contempt of others. I hated myself for my inability to feel better. Wasn’t I treating myself for alcoholism by attending support groups? What was I doing wrong to keep that from working?

I felt contempt from some members of support groups for my intractable longing to drink and intractable unhappiness. Not feeling better was my fault. I was doing things right enough, but I wasn’t being right. I was selfish and prideful and egotistical because I would not subsume my identity beneath the identity of a power greater than myself.

Brené Brown defines shame as “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging – something we’ve experienced, done, or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection.”

“Shame and stigma are the exact opposite of what fights addiction.”

– Maia Szalavitz, letter to the New York Times, 2/3/16

How in the world did I end up so excruciatingly scorned by myself, by people close to me, by society as a whole?!

Friends and people who know of my anguish and have started reading Maia Szalavitz’s Unbroken Brain universally start their next conversations with me, “Oh, Anne. Now I understand.”

Yes. I understand now, too.

“For those moving from experience-based and belief-based addictions treatment to evidence-based treatment, i.e., for those familiar with the research on addiction, Szalavitz’s book [Unbroken Brain] is not controversial, but masterful…In her weaving of personal narrative, scholarly knowledge of the evidence, logic that feels like she has intimate knowledge of how the reader thinks best, skillful, artful writing, and sheer, awe-inspiring intellect, Szalavitz jettisons the foolish and unfounded and, from the remaining discord of what the science says, creates a treatise on addiction as concise, exquisite and moving as poetry.”

– excerpt from my piece on Unbroken Brain for The Fix

In my “post-Maia life,” as my cognitive dissonance helps me confront and make new sense of a 10-year struggle with addiction, what I understand is how deeply, profoundly and harmfully I have misunderstood addiction. Foremost among my new understandings is that support isn’t treatment. My misunderstandings have hurt me and others.

No more.

. . . . .

When I finished Unbroken Brain, I started reading everything I could by Maia Szalavitz. On May 11, I tweeted Maia Szalavitz about a possible speaking gig. And she replied.

Maia Szalavitz, author of Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, has graciously agreed to speak in my hometown of Blacksburg, Virginia on Wednesday, August 3, 2016.

Learn more about Maia Szalavitz’s visit to Blacksburg, Virginia