I know I need to take a vacation and I’ve been urged by mentors to take a vacation. But it’s so hard…

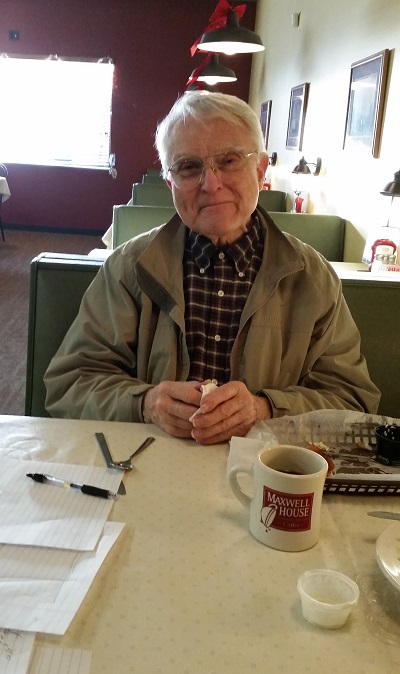

Over the past few weeks at our frequent meals at Famous Anthony’s, my father has been explaining optimization within constraints to me with diagrams like these. Alex Edelman wrote a definition of the concept in his signature style, opening with my fav, in medias res: “You are dropped on an alien planet and told to climb the highest mountain.”

Over the past few weeks at our frequent meals at Famous Anthony’s, my father has been explaining optimization within constraints to me with diagrams like these. Alex Edelman wrote a definition of the concept in his signature style, opening with my fav, in medias res: “You are dropped on an alien planet and told to climb the highest mountain.”

For me, that scenario is identical to contemplating a vacation.

I’ve been on a total of five vacations, three with my family as a child, one with my first husband, and one with my second. That’s an average of just under one vacation per decade. Vacations are alien to me, uncommon, unfamiliar.

And the “highest mountain” expectations for a vacation exhaust me. After everything that’s gone down, especially in the past decade, “highest” anything just doesn’t seem possible for me.

I have a fifteen year-old back injury that makes sitting painful; long car rides and plane rides feel like unanesthetized surgical procedures requiring silent endurance before any fun can begin. After about thirty minutes in a car, I start feeling stiff and trapped. My 2001 Honda has 96,000 miles on it.

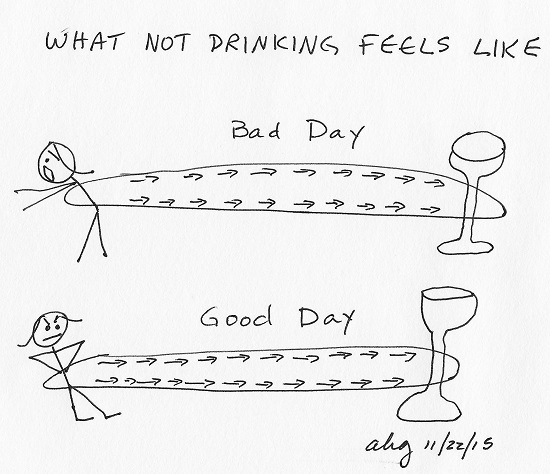

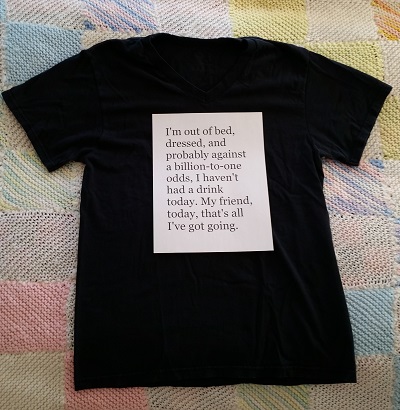

Then I have the one billion practices and activities required to maintain abstinence from alcohol: vigilance about being with others drinking alcohol, intense exercise, enough social interaction to heal my brain, not so much to fry my little introverted soul, eat this, not that, on and on…

I can’t go anywhere or do anything.

At Famous Anthony’s, I told my father woefully of all my “can’ts.” He started drawing lines on a sheet paper, limit after limit, constraint after constraint, until only a little white block was left in the center. And then he tapped his pen at the center and looked into my eyes, his brown eyes just like mine. And as only my intelligent, learned, passionate, kind father can do, he leaned forward and said, “Here. Here is where you are free.”

Not solely bound by life’s happenings? Free to optimize, to maximize, to go my “highest” within my own personal little white block?

Free to optimize what I can control of my life – even a vacation?

Well, then, I would absolutely love a long stay at a remote, technology-free, workout-friendly, luxurious spa, beamed painlessly there by a Star Trek transporter.

I first heard the term staycation from travel expert Kelly Queijo, founder of Smart College Visit.

From Monday, January 4, through Friday, January 8, 2015, I’m going on a staycation in my own personal little white block of freedom! I’m going to the faraway spa of Blacksburg, Virginia. I can create the remoteness through choice and self-discipline. No computer, no Internet, no phone (except for calls from my father). No texting? No Facebook? Yep to nope!

Using Debra Bass’s advice to plan for a staycation like a “real” vacation, I’ve asked friends for suggestions and am starting to make lists of their ideas for spa-like luxuries I can create in my own home and do in my own hometown. And all my oh-so-carefully constructed abstinence structure will still be safely in place. I can just fall back into what delights, restores and soothes me. Brings tears to my eyes!

A staycation on my own little alien planet with a terrain I can handle.

I’m not sure what other daughters thank their fathers for teaching them, but I thank my dad for teaching me how to sharpen a pocketknife, make French toast, and optimize within constraints. These lessons will delight, restore and soothe me the rest of my life.