“…before everything got written so far wrong.”

– from “Liquid Paper” in Liquid Paper: New and Selected Poems by Peter Meinke

“Everything got written so far wrong” when I tried to stop drinking and couldn’t.

I felt horror and sorrow. I felt determined to find out why and what it meant. I felt enraged and ashamed.

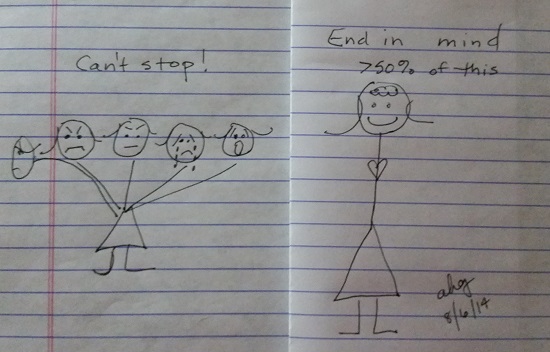

I drew my feelings this morning in the order in which they came to me, right to left.

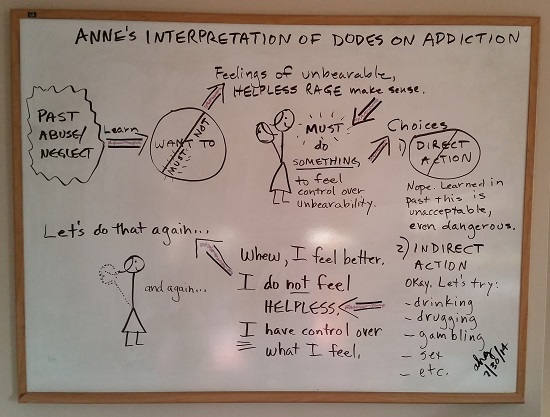

I began this blog on August 17, 2013 with this “end in mind” drawing. I could no longer keep my writing voice silent, but I kept secret what was most plaguing me – that I was 7 1/2 months abstinent from alcohol and writhing.

On July 28, 2014, I had been abstinent from alcohol for 19 months. I am writhing less. But I am appalled at how hard abstinence is for me. Others early in abstinence, or trying to become abstinent, share their stories with me and they writhe, too.

Unacceptable.

That determined face is the one that’s writing.