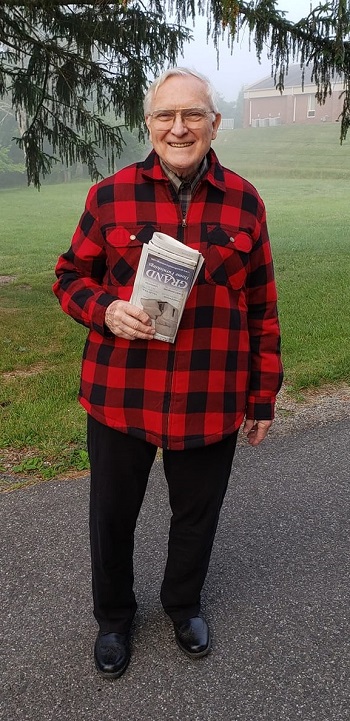

To: Robert H. Giles, Jr., Ph.D., Virginia Tech Professor Emeritus

From: The Universe

Dear Bob,

This is to acknowledge your extended service to The Universe.

First, we want to affirm your understandings. For all meaningful human purposes, you are correct that the universe is so complex as to appear random and chaotic. Within that complexity, however, reasonable probabilities can be calculated. Therefore, we confirm that your idea to use a systems approach with natural resource management, and then to apply a systems approach to pretty much everything, was sound.

Your genes, your choices, and your luck determine your life span. Your luck ran out and your brain began to degenerate. You were correct that life without a functioning brain is a limited life, indeed. Your wish to The Universe was to contribute to science. You have done so and, as you surmised, can contribute no more. We await the donation of your body to science as your final act of service.

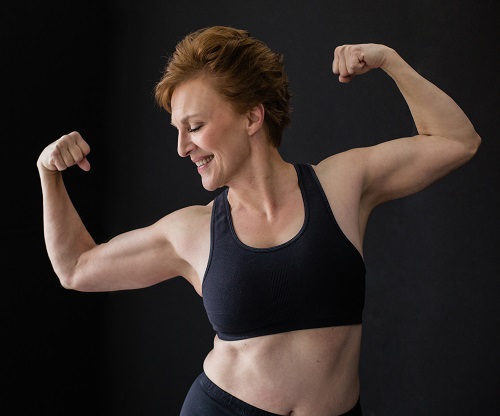

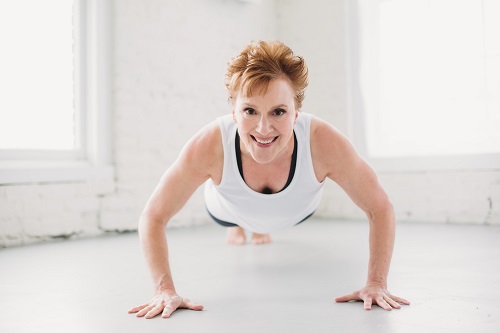

That said, on the rarest of occasions, for no reason we can or will convey to you, The Universe sometimes senses tiny, flaming bursts of on-going anguish. We noted this in one Anne Giles, your eldest daughter, resident of Blacksburg, Virginia, U.S.A. She was caught home alone, partnerless and childless, during a global lockdown, during a pandemic. There is a level of despair that does not cause death, but creates a living death. She was on the precipice.

Although we sensed your anguish and your despair, we also sensed that you sensed your daughter’s distress. Simply put, she may have needed you in order to make it through.

We are not sure how you did it, but, perhaps as an Eagle Scout, as a past-President of the Virginia Tech Corps of Cadets, as an Army Ranger, as a Wine Award-winning teacher and scholar, you felt called to service beyond your own needs and wishes. In the context of random chaos, we cannot know one way or the other if she would have been able to gather herself without you. Given the 300,000-year history of Homo sapiens, among the 100 billion people who have ever lived, the odds of her life making a difference are nearly zero.

The secret about despair, though, is that a person has to love her life to care enough to despair for it.

Do you or your daughter deserve notice from the universe? You neither deserve not do not deserve it. This letter may seem real but the data suggests this is a work of the imagination and not real at all. We cannot know for sure.

Nonetheless, in a rare commendation, The Universe thanks you for sacrificing your peace for hers. Her memories from the pandemic are anchored in what appeared to be her greeting and parting hugs every time she visited you in your assisted living facility, but were really her holding onto your thinning shoulders for dear life.

Of all the people left on the planet, you were the one she had known and loved – and been loved by – the longest. Instead of toppling end over end in our chaos, she held onto you.

In the midst of the direst time in the last 100 years of human history, you were unable to speak in ways that made sense. Yet, you still showed her and gave her what lasts and what matters, at least in the human universe: Deliberating choosing values. Deliberating living by them. Choosing what one says and does, even in the end. Love.

When you were a young man, The Universe heard your musings, while your young daughter also listened, about the measure of one’s love. “To love unto death?” you asked, looking up at our moon and stars.

Bob, mission accomplished. In the context of your sacrifice and love, you gave your eldest daughter time to find a new inner strength and presence that will carry her through to her end.

The Universe usually is neutral, neither caring nor not caring about the 100 billion humans who have lived on one of its planets. But, Bob, truly, really? With only strands left of who you could be, you chose love? We take note.

We see no more for you to do, Bob. You are welcome to stay or go, your choice. Yours has been a life nobly-lived.

With respect,

The Universe