Being a person who gives or coordinates care for a person with the set of symptoms termed “dementia” is a rare occurrence.

Currently, approximately 88% of the U.S. population aged 65 and older and 93-95% of the world’s population aged 60 and older have not developed symptoms of dementia. While the number of people with dementia is expected to increase through 2050, percentages are not.

Being a person who cares for a person with dementia is also a nearly singular experience, having some common and also unparalleled elements with other caregiver roles.

Rather than a diagnosis, “dementia” is the term for a set of symptoms resulting from brain-damaging diseases such as Alzheimer’s and others. This damage to the brain results in reduction of memory, ability to recall and form words, ability to use logic and reason, ability to learn new information, and other reductions in abilities.

As brain-damaging diseases begin to cause the set of symptoms termed “dementia,” brain networks reroute to bypass the damage. As the damaged portions accumulate, brain networks can no longer bypass the extensive areas of damage. Mental and physical functionality declines. Intermittently, functionality may return due to unknown re-routings or temporary reconnections. The causal disease is difficult to determine and usually requires an autopsy to accurately diagnose.

Dementia, resulting from one or more illnesses, is progressive and irreversible. There is no effective treatment or cure.

In caring for a terminally ill person without cognitive impairments, a caregiver witnesses the declining health of the person for whom they are caring. A caregiver for a person with a degenerative cognitive impairment, such as dementia, witnesses erasure of personhood, as well as declining health.

The human brain has evolved to work effectively with the reality of its environment. Most people, most of the time, behave within a predictable range. When the very essence of what makes a person human deteriorates before a caregiver’s eyes, and the person continues to live but speaks and acts in ways that seem inhuman, the experience for the caregiver can seem other-worldly, even horrific.

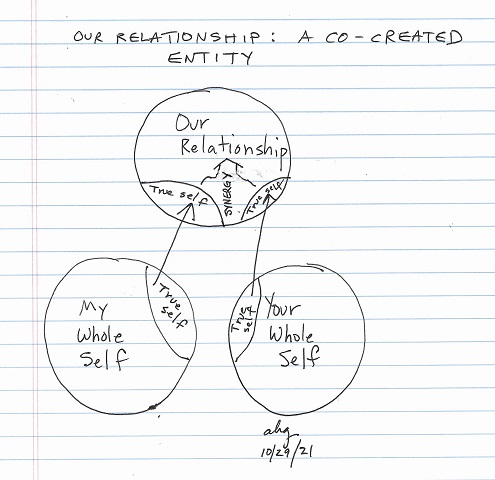

As a result of challenges to their reality created by this illness, caregivers can experience a devastating loss of connection with the self and the self’s inner resources: losses in self-awareness, self-empathy, self-compassion, self-efficacy, invention and creativity, and inner wisdom.

On an on-going basis, witnessing the person’s suffering, their abnormal words and actions, paired with experiencing the loss of connection with self, and connection with the person even though they sit or stand in front of them, can seem surreal, disorienting, harrowing, traumatic, and painful to the point of being torturous, calling into question the caregiver’s own reality, even the very meaning and purpose of existence. The caregiver’s suffering can be acute.

I have created “A Self-Assessment and Tool for People Who Serve as Caregivers for People with Dementia.” The 8-page .pdf elaborates upon the content of this post and includes the self-assessment and tool. The document contains approximately 2,500 words.

The self-assessment and tool attempt to synthesize research findings on the experience of people who serve as caregivers for people with dementia, research on effective treatment for trauma, and research-backed elements of therapies derived from cognitive theory and other therapies, to ease the particular suffering of the person who serves as a caregiver for a person with dementia.

Of possible additional assistance

- Existential Concerns of People Who Care for People with Dementia

- Self-Help for Caregivers with Existential Distress (.pdf)

- What I Wish I Had Been Told About Dementia (forthcoming)

- Self-Help Guide for Reducing Trauma Symptoms

- Becoming One’s Own Cognitive Therapist

- Dementia Caregiver category on this site

With questions or comments, please contact me.

A Self-Assessment and Tool for People Who Serve as Caregivers for People with Dementia

Personal essay: What I Wish I Had Been Told About Dementia, 12/27/21

. . . . .

Selection of sources consulted (listed with inconsistent citation format):

Albinsson L, Strang P. Existential concerns of families of late-stage dementia patients: questions of freedom, choices, isolation, death, and meaning. J Palliat Med. 2003 Apr;6(2):225-35. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978470. PMID: 12854939.

Applebaum AJ, Kryza-Lacombe M, Buthorn J, DeRosa A, Corner G, Diamond EL. Existential distress among caregivers of patients with brain tumors: a review of the literature. Neurooncol Pract. 2016 Dec;3(4):232-244. doi: 10.1093/nop/npv060. Epub 2015 Dec 8. PMID: 31385976; PMCID: PMC6657396.

Day J, Higgins I. Existential Absence: The Lived Experience of Family Members During Their Older Loved One’s Delirium. Qual Health Res. 2015 Dec;25(12):1700-18. doi: 10.1177/1049732314568321. Epub 2015 Jan 20. PMID: 25605755.

Freter, Björn. On the Existential Situation of a Person with Dementia: The Drama of Mankind is repeated in the Drama of Dementia

October 2015 Journal of Health Science 3(5):205-216

DOI:10.17265/2328-7136/2015.05.002

Galfin JM, Watkins ER, Harlow T. A brief guided self-help intervention for psychological distress in palliative care patients: a randomised controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2012 Apr;26(3):197-205. doi: 10.1177/0269216311414757. Epub 2011 Aug 1. PMID: 21807750.

Kühnel MB, Marchioro L, Deffner V, Bausewein C, Seidl H, Siebert S, Fegg M. How short is too short? A randomised controlled trial evaluating short-term existential behavioural therapy for informal caregivers of palliative patients. Palliat Med. 2020 Jun;34(6):806-816. doi: 10.1177/0269216320911595. Epub 2020 Apr 29. PMID: 32348699; PMCID: PMC7243077.

Schulz R, McGinnis KA, Zhang S, Martire LM, Hebert RS, Beach SR, Zdaniuk B, Czaja SJ, Belle SH. Dementia patient suffering and caregiver depression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008 Apr-Jun;22(2):170-6. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653cc. PMID: 18525290; PMCID: PMC2782456.

Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Sinclair S, Karvinen I, Egan R, Speck P, Powell RA, Deskur-Smielecka E, Glajchen M, Adler S, Puchalski C, Hunter J, Gikaara N, Hope J; InSpirit Collaborative. Patients’ and caregivers’ needs, experiences, preferences and research priorities in spiritual care: A focus group study across nine countries. Palliat Med. 2018 Jan;32(1):216-230. doi: 10.1177/0269216317734954. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29020846; PMCID: PMC5758929.

Sellars M, Chung O, Nolte L, Tong A, Pond D, Fetherstonhaugh D, McInerney F, Sinclair C, Detering KM. Perspectives of people with dementia and carers on advance care planning and end-of-life care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliat Med. 2019 Mar;33(3):274-290. doi: 10.1177/0269216318809571. Epub 2018 Nov 8. PMID: 30404576; PMCID: PMC6376607.

Last updated 1/13/22 with link to Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, 1/6/22 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8

Wander van der Vaart and Rosanna van Oudenaarden. The practice of dealing with existential questions in long-term elderly care. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Well-Being, 2018.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.

The person with dementia may involuntarily gaslight the person who serves as the caregiver.

The person with dementia may involuntarily gaslight the person who serves as the caregiver.