The pandemic has created a new environment for anxiety: some of our formerly fantastical worries are now grounded in reality. Although cognitive-based therapies term unrealistic fears “cognitive distortions” and “patterns of problematic thinking,” some of what we feared might occur is actually happening in our homes, towns, and countries.

The human brain has evolved to handle hardship, however. In the brain, emotion-related regions and executive functioning regions work in synergy together, using feelings and thoughts as data to ease distress and solve problems. The term “inner wisdom” can be used to describe this brain function.

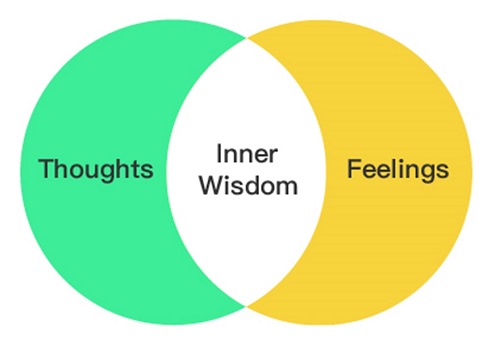

A helpful way to envision inner wisdom comes from an adaption of the concept of “Wise Mind” from dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). If feelings and thoughts are imagined as circles in a Venn diagram, the overlap between them offers the powerful synergy of each and both.

The challenge with fear, anxiety, and worry is that they highly activate the emotion-related regions of the brain, overwhelming the executive functioning regions and making inner wisdom difficult to access.

If I keep repeating worried thoughts to myself, I keep activating the emotion centers of my brain. The circle representing my feelings covers the circle representing my thoughts, limiting my access to the thinking regions of my brain, including the prefrontal cortex, and to the inner wisdom inherent in awareness of both feelings and thoughts.

Self-judgment and self-criticism – “I shouldn’t be feeling or thinking this way” – further exacerbate the dominance of my brain’s emotion centers.

Feeling anxious about feeling anxious – “Oh, no! Here comes anxiety again!” – does the same.

Trying to avoid what I’m feeling or thinking – or trying to distract myself from them – interfere with my brain’s ability to handle what’s happening. Avoidance and distraction divert me from my brain’s ability to help myself see what’s what and to do what needs to be done.

How can I stay present for both my feelings and thoughts and help my brain use its natural system to help me out during these hard times?

See if this inner narrative and these questions might help.

. . . . .

I have become aware I am having a thought about which I feel anxious.

- How realistic is this thought? What are the facts? (Many thoughts have some basis in reality. I can ask myself: On a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is “It’s a fact verified by rigorous science,” and 1 is “I’m truly guessing,” how reality-based/fact-based is the thought?)

- How effective is this thought? Is it producing the results I want?

- How likely is the content of the thought to happen? On a probability line, where would I place the chances? 100% certain, a 50%-50% chance, impossible?

- Is my beautiful brain engaged in negativity bias, thinking it needs to more heavily weigh everything that might be a problem in order to keep me alive?

- Am I focusing on thoughts about one part of a situation and not taking into account other parts of the situation? Am I weighing one part of the situation more heavily than other parts? Is this merited?

- Have I thought this thought before? Have I given it due time?

- If noodling over this thought would have “fixed” it, might I have noodled enough to fix it by now? Might I try another approach?

- How helpful is the thought? Is it helping me feel better or worse? Is it helping me do better or do worse?

- Is the thought helping me feel more hopeful or more despairing?

- Is this thought scaring me or reassuring me?

- Is the thought related to judgment – which distresses me further – or acceptance, which helps ease my distress?

- What are the top 3 facts/realities I need to accept about what happened/what’s happening?

- Right here, right now, am I okay enough, at least for now?

- Regardless of any of my answers, how can I help myself with this?

I can feel what I feel, think what I think, and also shift my attention to thoughts that help me feel better, do better, and produce the results I would like.

. . . . .

Even attempting to formulate the words in these questions activates the thinking portions of the brain. As one client puts it – for which I’ve been given permission to share – we can purposefully “Get cognitive!” Although stated perhaps simplistically, the “thinking circle” in the brain shifts the “feelings circle” back to its place of providing helpful data and synergy for problem-solving.

The questions can help people become aware of the relationship between events, feelings, and thoughts. This cornerstone of cognitive-based therapies is often explained using an “ABC Worksheet”:

- A – activating events result in

- B – beliefs/thoughts and

- C – consequences/feelings.

Here’s a .pdf entitled “ABC Worksheet – Pandemic Version” of the classic ABC worksheet with questions related to helping us through very challenging circumstances.

If you need help using these questions or want to further explore the ABC Worksheet or cognitive therapies, you’re encouraged to seek professional support.

Using our hearts and minds, plus the power of our beautiful brains, we can help ourselves through hardships – even through pandemics.

The content of this post is informed by Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Positive Psychology, and other work. it was synthesized and compiled by Anne Giles, M.A., M.S., L.P.C.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.