Humans have used substances for over 12,000 years in ways that are meaningful to them. Between 70-80% of people who use drugs do so without issue. In the U.S., an estimated 1 in 10 who use drugs develops a substance use disorder, also termed “addiction,” usually predicated by trauma and/or mental illness. Although chronic cases exist, most people with substance use concerns recover on their own without treatment.

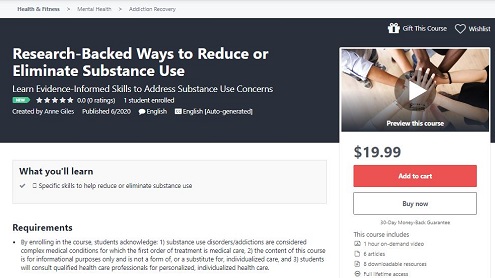

In this context, I am delighted to announce the acceptance by Udemy of our course “Research-Backed Ways to Reduce or Eliminate Substance Use.” In tandem with medical care, people can learn skills to self-administer counseling for substance use concerns.

I use the term “our” because this labor of love was co-created by me, clients, and community members. I scoured the research for what helps people with substance use concerns. Clients and community members field-tested exercises based on those findings. Since substance use is moralized, stigmatized, and criminalized, I can’t publicly thank the hundreds of people who contributed to creating this course. But I profoundly thank them for their bravery and leadership.

I can openly thank neuroscience journalist Maia Szalavitz, author of New York Times bestseller Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, for consulting on the course’s content. And I can openly thank Sanjay Kishore, M.D., who reviewed the content on requesting medical care.

Important: This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.

The current climate of tolerance of use of some drugs – caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol – and intolerance of use of other drugs – marijuana, methamphetamine, and heroin, for example, currently of interest to the media – leaves people who use drugs subject to moral, economic, and criminal, abstinence-only “treatment.”

Research is clear, however, on the skills and tools that help people reduce or end substance use. (If you are mandated to abstinence, this guide provides an overview of helpful skills.) This hour-long course offers research-informed lectures, assessments, and exercises for people who wish to learn more about evidence-based treatment for substance use concerns, beginning with medical care.

I recorded the videos over two days at my home using my laptop’s camera. I wondered if a cat might wander though the screen but not this time.

I welcome your reviews and feedback. I welcome your contributions to this course being as helpful as possible.

I am so gratified that Udemy accepted our course. Since I am only licensed to offer counseling services in Virginia, this is a way for anyone, anywhere to access what research suggests is helpful. Here are the resources linked to from the course.

I wish you the very best. If I can be of service in any way, please do not hesitate to contact me.

“I was in hell,” she said. “And I made a vow: when I get out, I’m going to come back and get others out of here.”

– Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., founder of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), quoted in the New York Times and expanded upon in her 2020 memoir, Building a Life Worth Living

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.

While some accuse me of making a “choice” to use, or selfishness for “liking to get high,” or of having moral or criminal problems, addiction research does not support these beliefs. My original use may have been of my own volition, but with repeated, extensive use over time, my brain learned to use nearly automatically. Because alterations occurred in the organ of the brain, this condition is alternately termed a “disease,” a “medical illness,” a “brain disorder,” a “health problem,” and a “health condition.”

While some accuse me of making a “choice” to use, or selfishness for “liking to get high,” or of having moral or criminal problems, addiction research does not support these beliefs. My original use may have been of my own volition, but with repeated, extensive use over time, my brain learned to use nearly automatically. Because alterations occurred in the organ of the brain, this condition is alternately termed a “disease,” a “medical illness,” a “brain disorder,” a “health problem,” and a “health condition.”