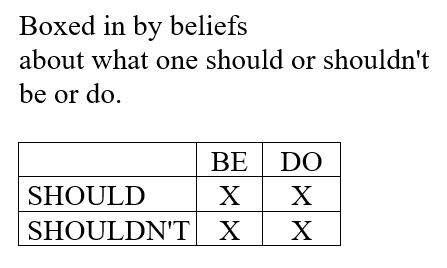

Please fill in the blanks with the first thought that comes to mind.

I. Become aware of one’s thinking about life.

“Life should provide __________. Life should have __________. If life doesn’t provide or have __________, life is not as valuable as it would otherwise have been.”

Become aware of the interrelationship between what happens, thoughts that are belief-based or wish-based, thoughts that are fact-based, and feelings.

“When __________ happened, I thought it shouldn’t have happened because life shouldn’t be that way. I shouldn’t have to __________. Since life should have __________and should provide __________. I felt betrayed because I trusted life to be the way I believed it was and should be. I felt disappointed in myself, in others, and in my life.”

II. Become aware of one’s thinking about one’s self.

“I should (circle) feel/think/do/have __________. If I don’t, I am not as valuable as I would otherwise have been. If I am not as valuable as I could be, I will not be adequately appreciated or loved. If I am not adequately appreciated or loved, I experience unbearable pain.”

Again, become aware of the interrelationship between what happens, thoughts that are belief-based or wish-based, thoughts that are fact-based, and feelings.

“When ______ happened to me, I thought it shouldn’t have happened. I thought that if I had said or done something different, or were different, it wouldn’t have happened. I believe I am responsible for how people feel, think, act, and are doing and, thus, I failed. This made it my fault and I was to blame. I judged myself as incorrect, incompetent, and inadequate. I felt ashamed of myself. From these reprimands, I felt overwhelmed with pain.”

III. Are the thoughts realistic?

“Reality is complex. Some aspects of my thoughts are realistic; some aspects aren’t. If I imagine a pie chart:

In January 2020, I estimate ____% of my thoughts were realistic and _____% were unrealistic.

Today, in 2023, I estimate ____% of my thoughts are realistic and _____% are unrealistic.”

IV. How can I help myself?

- I can see reality as it is.

- Within reality, realism gives me power. I neither idealize nor vilify, not myself, others, institutions, or the world.

- I am real. I am not composed of other people’s beliefs, expectations, needs, and wants. I am not the victim of life, of how I was born, of how I was raised, or of what’s happened to me. I co-travel with my traits and my history.

- As a result of making heroic, conscious choices to see reality as it is, I can identify problems and create solutions. I can adjust, adapt, and accept as needed.

- I can become aware of self-judgment and replace it with

self-kindness. Prolonged, inner states of activated intensity, and of under-activated despondency, frequently result from two sources: harsh self-judgment and envisioning being harshly judged by others. - As a result of awareness and self-kindness, I can use my inner dialogue to regulate my emotions at will.

- Although I wish I had one or more people to appreciate and love me adequately, I see that, even if I did, during most of the 168 hours of each week, I’m on the job solo. I’m responsible for my inner state.

- I may have some influence but cannot cause what human adults feel, think, want, say, or do. I am not causal. Why not? Human adults are separate, independent, autonomous beings who choose their own words and actions.

- Unless I attempt to violate their independence by using emotional, relational, financial, and/or sexual favors, or persuasion, manipulation, shame, coercion, and/or force, I co-travel with the decisions other humans make.

- I appreciate and love myself for handling the joys and sorrows of the human condition. I can feel compassion for everyone, everywhere, for having to handle the same.

V. My primary tasks are:

- to discover and understand my values, strengths, preferences, interests, and priorities;

- to become aware of what I need and want;

- to identify unmet needs and unfulfilled aspirations;

- to estimate what’s likely and unlikely;

- to see that opposites can both be true, that most factors occur within the context of a continuum, not as all good or all bad;

- to derive strategies to help myself precisely with what

I want to do, not with a) what I wish or want others to do, or

b) what others want from me; - to shift and re-shift my attention to my values and priorities;

- to do what I define as mine to do in the time I have.

VI. How else?

Given the broad goals of making a life for myself and being of service to others, given the constraints of 2023 and the uncertainties of the future, how else might I help myself?

VII. Clarity

To the tasks of being myself, of navigating the opportunities and hardships inherent to the human condition, in my situation, in these times:

The primary personal strength I bring is __________________.

The primary value powering my efforts is __________________.

The primary priority giving me direction is __________________.

. . . . .

Therapy protocols derived before 2020 held a fundamental premise. People were free to take independent action on their own behalf.

In particular, cognitive theory celebrated human capability. Once individuals became aware of what they were feeling and thinking and directed their attention to reality-based thoughts, they could then build lives and relationships based on reality as perceived by logic, reason, and evidence.

For the past three years, I have heard an on-going note of distress in the narratives of many of the clients I met with online, in the thousands of voices I heard in the listening, watching, and reading I did during these years of isolation, and in my own inner experience.

Indeed, awareness, itself, can ease distress, regardless of the situation, even the most dire. This is the core of existential therapist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s premise. During the pandemic, surely, we had the time to become aware.

However, engagement in action and engagement with others are the mechanisms by which awareness is directed toward effective, skillful living. With limited opportunities to leave our dwellings and connect with people, the limits of current therapy protocols were exposed.

I posit that cognitive theory-based protocols need an update that emphasizes self-reliance. Why? Our ability to take action and to connect with others was truncated. The external was impossible. The internal was possible.

This post is an an imagining of the pandemic-informed worksheet that would be added to updated, 2023 editions of cognitive theory-based manuals, such as Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual by Patricia A. Resick, Candice M. Monson, and Kathleen M. Chard, Guillford Press, 2016.

At essence, this worksheet champions and fosters the powerfully kind and determined inner dialogue that sustains and guides when one is on one’s own.

. . . . .

To explore and discover tools and insights related to the tasks, I use the term “awareness skills” and have them outlined in about 3,000 words here.

Image: iStock

All content on this site is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical, professional, and/or legal advice. Consult a qualified professional for personalized medical, professional, and legal advice.