The following is a plain language summary of how counseling works. With great assistance from Chinese instructors, I have written what I can in both Simplified Chinese Characters and English. What remains in English is still beyond my vocabulary to translate. For myself and others learning to read Simplified Characters, pinyin is included.

心理咨询如何用简单的语言总结

xīnlǐ zīxún rúhé yòng jiǎndān de yǔyán zǒngjié

A Plain Language Summary of How Counseling Works

在西方的心理咨询中,我们把“内心体会”定义为意识的感受和想法。平时,在东方的思维方式中,感觉和想法是在一起的,不是分开的。

Zài xīfāng de xīnlǐ zīxún zhōng, wǒmen bǎ “nèixīn tǐhuì” dìngyì wéi yìshí de gǎnshòu hé xiǎngfǎ. Píngshí, zài dōngfāng de sīwéi fāngshì zhōng, gǎnjué hé xiǎngfǎ shì zài yīqǐ de, bùshì fēnkāi de.

In western counseling, our “inner experience” is defined as awareness / consciousness of feelings and thoughts. Usually, in eastern thought, feelings and thoughts are seen as together, not separate.

无论从东方还是西方,人类都希望能用他们的意志力解决问题。

Wúlùn cóng dōngfāng háishì xīfāng, rénlèi dōu xīwàng néng yòng tāmen de yìzhì lì jiějué wèntí.

Whether from east or west, all humans want to be able to solve problems using their willpower.

然而,在西方的心理咨询中这是假设:如果人们成为意识到自己的感受和想法, 这创造了一个远景. 在这个远景中,也许就看到了解决问题的可能性。当人们看到现实的本来面目时可能性就会打开。

Rán’ér, zài xīfāng de xīnlǐ zīxún zhōng zhè shì jiǎshè: Rúguǒ rénmen chéngwéi yìshí dào zìjǐ degǎnshòu hé xiǎngfǎ, zhè chuàngzàole yīgè yuǎnjǐng. Zài zhège yuǎnjǐng zhōng, yěxǔ jiù kàn dào liǎo jiějué wèntí de kěnéng xìng. Dāng rénmen kàn dào xiànshí de běnlái miànmù shí kěnéng xìng jiù huì dǎkāi.

However, in western counseling, this is the hypothesis: If people can become aware of their feelings and thoughts, a vista opens. In that vista, possibilities for solving problems can be seen. When people see reality as it is, possibilities open.

所以,解决个人问题时,和使用意志力相比,意识对我们的内心体会有更帮助.

Suǒyǐ, jiějué gèrén wèntí shí, hé shǐyòng yìzhì lì xiāng bǐ, yìshí duì wǒmen de nèixīn tǐhuì yǒu gèng bāngzhù.

Therefore, for solving personal problems, compared to using willpower, it is more helpful to use our awareness of our inner experience.

. . . . .

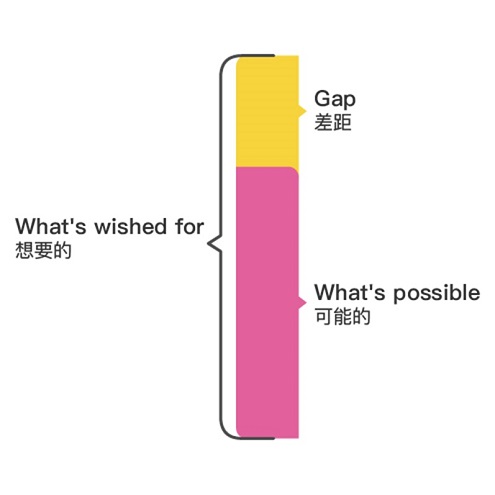

所想要的和可能的之间的差距导致了我们内心的痛苦。

Suǒ xiǎng yào de hé kěnéng de zhī jiān de chājù dǎozhìle wǒmen nèixīn de tòngkǔ.

The gap between what is wished for and what is possible causes our inner pain and suffering.

为了帮助我们内心的痛苦:

Wèile bāngzhù wǒmen nèixīn de tòngkǔ:

To help with our suffering:

第一,我们会帮助你对这差距导致的痛苦使用自我慈悲。我们用自我仁慈来安慰自己。

Dì yī, wǒmen huì bāngzhù nǐ duì zhè chājù dǎozhì de tòngkǔ shǐyòng zìwǒ cíbēi. Wǒmen yòng zìwǒ réncí lái ānwèi zìjǐ.

First, we use self-compassion to help ease the inner pain created by the gap. We comfort ourselves with self-kindness.

自我慈悲 zìwǒ cíbēi self-compassion

自我仁慈 zìwǒ réncí self-kindness

第二,我们会帮助你慢慢地适应和接受什么是可能的。

Dì èr, wǒmen huì bāngzhù nǐ màn man de shìyìng hé jiēshòu shénme shì kěnéng de.

Second, with self-compassion and self-kindness, we help ourselves to slowly adjust to, adapt to, and accept what’s possible.

适应 shìyìng adjust, adapt

第三,我们发现价值观和优先事项,然后根据这些决定下一步。

Dì sān, wǒmen fāxiàn jiàzhíguān hé yōuxiān shìxiàng, ránhòu gēnjù zhèxiē juédìng xià yībù.

Third, we discover values and priorities, then, based on those, decide next steps.

价值观 jiàzhíguān values

优先事项 yōuxiān shìxiàng priorities

Here are some other terms and ideas that may be useful.

意识意识,了解 yìshí, liǎojiě awareness, consciousness

意识到 yìshí dào to become aware of

了解自己的心理 liǎojiě zìjǐ de xīnlǐ to understand one’s own

psychology; to be psychologically-minded

These concepts can overlap and intersect:

真实的自我 zhēnshí de zìwǒ true self; authentic, genuine, real self;

separate from, and unaffected by, external pressures 外在压力 wài zài

yālì, such as corporate, familial, religious, societal, cultural, or national expectations.

核心自我 héxīn zìwǒ core self; innate traits as an individual human;

stable and unaffected by external events, whether the events are

experienced as joyful or painful.

When I use the term “true self,” I am merging both of those concepts.

. . . . .

当人们看到现实的本来面目时可能性就会打开。

Dāng rénmen kàn dào xiànshí de běnlái miànmù shí kěnéng xìng jiù huì dǎkāi.

When people see reality as it is, possibilities open.

此外,当人们,不最小化也不最大化,看到现实的本来面目时可能性就会打开。

Cǐwài, dāng rénmen, bù zuìxiǎo huà yě bù zuìdà huà, kàn dào xiànshí de běnlái miànmù shí kěnéng xìng jiù huì dǎkāi.

Moreover, when people neither minimize nor maximize, but see reality as it is, possibilities open.

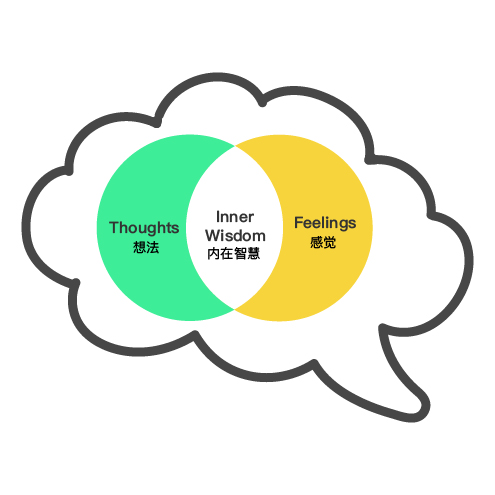

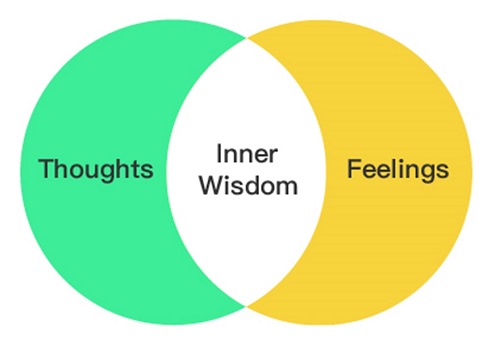

当事情一起发生并产生更大的积极影响时,协同效应就会发生。

Dāng shìqíng yīqǐ fāshēng bìng chǎnshēng gèng dà de jījí yǐngxiǎng shí, xiétóng xiàoyìng jiù huì fāshēng.

Synergy happens when things come together and create a bigger positive effect than they would alone.

当人们意识到他们的感受和想法时,协同效应产生了。这个可以成为”内在智慧 。“

Dāng rénmen yìshí dào tāmen de gǎnshòu hé xiǎngfǎ shí, xiétóng xiàoyìng chǎnshēngle. Zhège kěyǐ chéngwèi” nèizài zhìhuì.“

When people can become aware of their feelings and thoughts, synergy is created. That synergy can be termed “inner wisdom.”

协同效应 xiétóng xiàoyìng synergy

内在智慧 nèizài zhìhuì inner wisdom

Although “depression“ and “anxiety” are common terms, they are so diversely used and defined that they’re not very useful. Becoming aware of the real, specific, precise feelings and thoughts created by the gap between what one wished for, what has happened, and what is now possible – and then helping oneself with those feelings and thoughts – is more directly helpful.

Using their inner wisdom, people can become aware of their true self’s needs and wants, strengths and preferences, values and priorities, and derive strategies to live lives of integrity and personal meaning.

A comprehensive explanation of how to develop awareness skills is here.

. . . . .

有时候,当一个人经历过不好的事情时,它会觉得自己是受害者。他们需要夺回他们的”力“:自己力量,权力和生命力。

Yǒu shíhòu, dāng yīgè rén jīnglìguò bu hǎo de shìqíng shí, tā huì juédé zìjǐ shì shòuhài zhě. Tāmen xūyào duóhuí tāmen de” lì “: Zìjǐ lìliàng, quánlì hé shēngmìnglì.

Sometimes, when a person has a bad experience, they can feel like a victim. They need to get their power back: their personal power, their sense of authority, and their life force.

经历 jīnglì experience

受害者 shòuhài zhě victim

夺回 duóhuí take back

力量 lìliàng personal power

权力 quánlì authority; power

生命力 shēngmìnglì vitality; life force; power

怎么做?

Zěnme zuò?

How?

记得你的个人价值。

Jìdé nǐ de gèrén jiàzhí.

Remember your value.

从过去对你的价值观和优先事项上转移你的注意力.

Cóng guòqù duì nǐ de jiàzhíguān hé yōuxiān shìxiàng shàng zhuǎnyí nǐ de zhùyì lì.

Shift your attention from the past to your values and priorities.

转移 zhuǎnyí shift

注意力 zhùyì lì attention

价值观 jiàzhíguān values

优先事项 yōuxiān shìxiàng priorities

. . . . .

Stability results from providing care for one’s heart, mind, and body. To support personal growth and personal psychological work, people need as much stability as possible.

稳定 wěndìng stability

心灵, 思想, 和身体 xīnlíng, sīxiǎng, hé shēntǐ heart, mind, and body

- Here is a self-care checklist 自我安慰清单 zìwǒ ānwèi qīngdān.

- Here are exercises that can help people become aware of their

values and priorities 价值观 jiàzhíguān values | 优先事项 yōuxiān shìxiàng priorities.

. . . . .

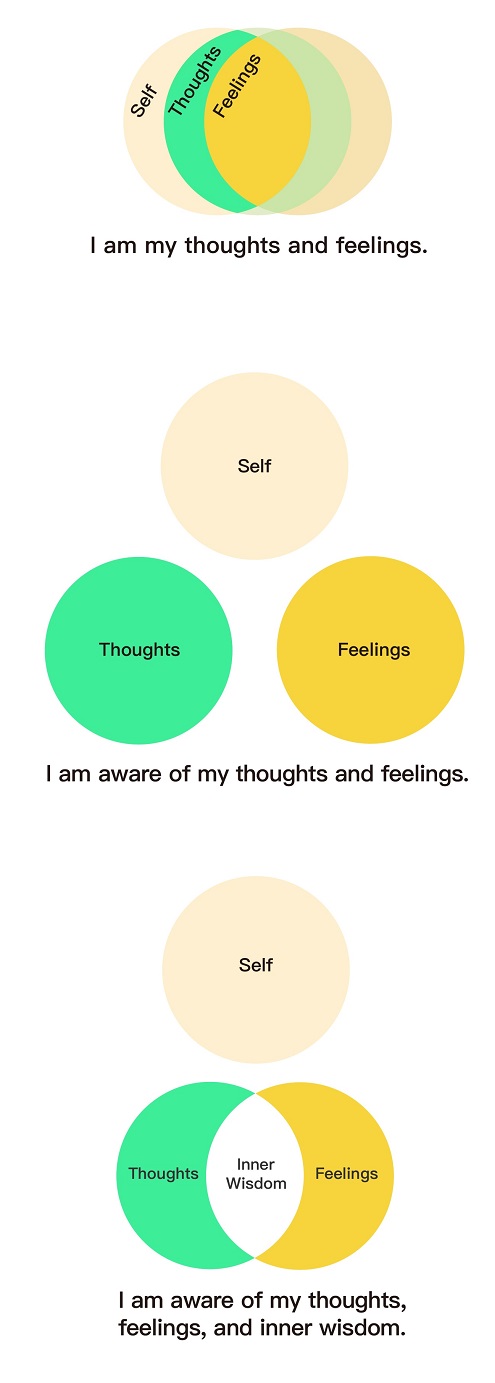

我是我的想法和感受。

我是我的想法和感受。

I am my thoughts and feelings.

我意识到我的想法和感受。

I am aware of my thoughts and feelings.

我意识到我的想法,感受,和内在智慧。

I am aware of my thoughts, feelings, and inner wisdom.

内在智慧 nèizài zhìhuì inner wisdom

The concept of “inner wisdom” is informed by:

- Dr. Marsha Linnehan’s conception of “Wise Mind”;

- cognitive theory;

- the findings from neuroscience research that the human brain’s structures include different areas for processing cognitions and emotions that interconnect and overlap.

The content of the post is informed by cognitive theory-based therapy protocols, including cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and cognitive processing therapy; acceptance and commitment therapy, (ACT), Internal Family Systems (IFS), schema therapy, strengths-based therapy protocols, and existential therapy.

The content is written in plain language to help people understand upon a first reading and to help dispel misinformation.

I am indebted to Hou Huiying for her help in translating these sentences. Any errors are mine.

Graphics by Ren Jing.

Last updated 9/12/2023

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.