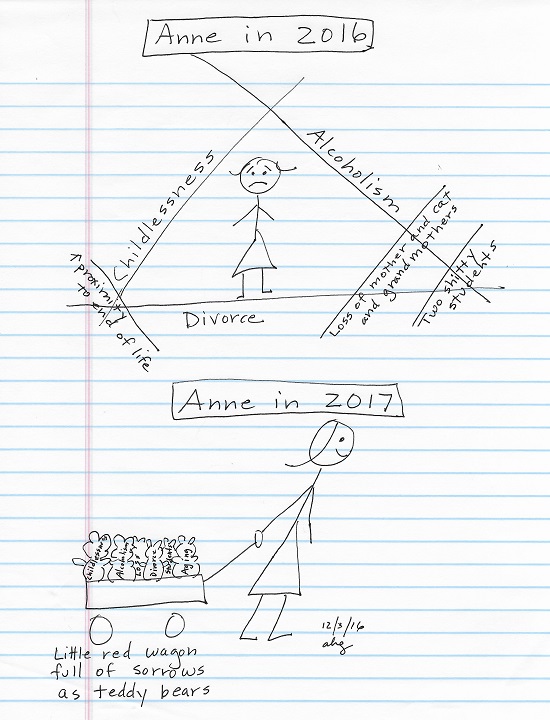

A Grown Woman Might Need a Little Red Wagon

How to Care for Yourself After a Shock

If something happened that shocked you, you can help yourself with it.

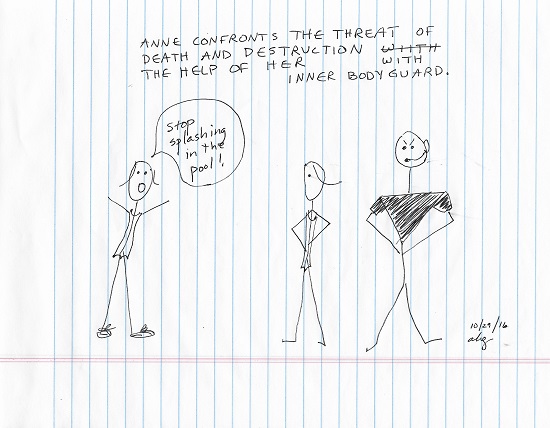

First, assess whether or not you are currently at risk or may be at risk within the next few minutes. If your situation is unsafe, get yourself to safety as quickly and efficiently as you can.

If you are in a safe enough place for now, hug yourself. Hug yourself hard.

Now. When we’re upset, even for the most legitimate, justifiable reasons, we can’t think. So our job is to “un-upset” ourselves enough to be able to balance feeling and thought so we can use our full powers to discern what would be effective action – or what would be effective inaction – on behalf of ourselves and others.

So. Here we go.

- Acknowledge to yourself that you have had a shock.

- Pause to become aware of your inner experience of the shock. What are you feeling, what are you thinking, what physical sensations are you having?

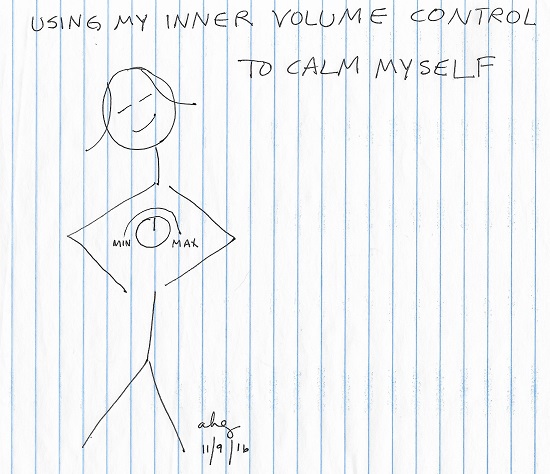

- Imagine a volume control knob representing the intensity of your inner experience, the totality of your feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations. On the “minimum” to “maximum” scale, note where the knob registers at this moment.

- Become aware of your breath. Note anything that draws your attention to your breath. Is your breathing rapid or slow? Deep or shallow? Simply notice this.

- Can you deepen, elongate or slow your breath? Even just a bit? If so, you are engaging in an already-in-place, mind-body hack that can begin the “un-upsetting.”

- Now become aware of your thoughts. When you become aware of a thought, imagine the volume control knob and observe what happens when you think the thought.

- If the thought increases the intensity of your inner experience, acknowledge it as a thought to consider later, but for now, for just a few moments, it is not helpful to you as you attempt to shift your inner volume. Disengage your attention from the unhelpful thought and engage your attention with the next thought.

- Simply note the effect of a thought on your inner volume control. Avoid attaching goodness or badness, rightness or wrongness to thoughts. Simply note their effect on you and disengage attention from the unhelpful ones.

- Continue to sort your thoughts, based on their impact on your inner volume control.

- While you’re sorting your thoughts, also monitor your inner volume control.

- Become intentional about using your mind to bring down the volume on your inner experience. There’s no particular how-to on this. How you do this will be unique to you.

- Note that thoughts that are self-judging, other-judging, replay what happened, anticipate future trouble, result in a sense of helplessness, or result in a feeling of outrage or alarm tend to increase the volume on one’s inner experience.

- Appreciate yourself for your fine mind and powerful thinking skills and then shift your attention from these thoughts back to sorting.

- Note your breath. See if you can inhale on a count that works for you, then exhale on the same count.

- Continue to sort thoughts and observe your inner volume control.

Become aware of when you experience the presence of your feelings, thoughts and bodily sensations falling within a manageable range. Then note when your inner volume is moving into an unhelpful range, whether too high or too low, and immediately shift your attention back to sorting unhelpful from helpful thoughts. Use your mind, in your own way, to shift your inner volume to a level that feels manageable to you.

The ability to manage your inner volume frees your inner wisdom – a wise, synergistic blend of both your rationality and emotionality – to help you decide what would be effective, helpful and beneficial for you to do in this moment and the next, no matter what has just happened – or what might or might not.

. . . . .

Maia Szalavitz introduced the idea of using the metaphor of a “volume knob” to represent regulating one’s inner experience in Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction, published in April, 2016.

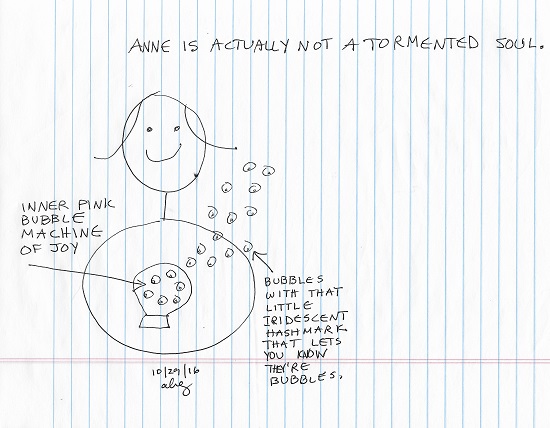

I, Actually, Am Not Tormented

Why I Can’t Join You for Thanksgiving

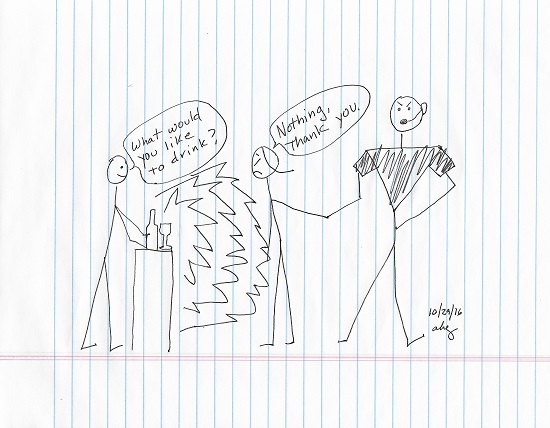

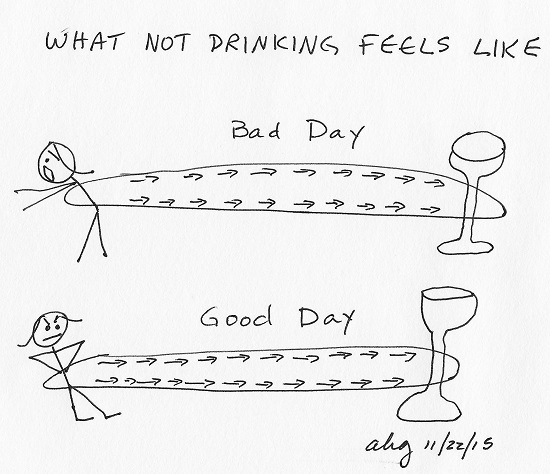

As I approach three years without a glass of wine – or beer or of any alcohol of any kind – I have wondered if my time of abstinence is a rubber band around my waist. The farther I walk away from that last glass of wine, the tighter it gets. The next step into the next day of abstinence may be the step that tightens the band beyond my strength and snaps me back to the wine I both love and loathe.

Lately, I have been dreaming of wine. In one recent dream, I pulled a single swallow of wine into my mouth then spit it out. I awakened with the conviction this was a turning point in my recovery, negating the rubber band analogy. I could, after all, of my own volition, stop myself. Ah, but the night before last, in my dream, I drank the wine, sneaking it into a glass of club soda, talking amiably with a person in recovery who was not drinking.

People suffering from addictions are not morally weak; they suffer a disease that has compromised something that the rest of us take for granted: the ability to exert will and follow through with it.

– Nora D. Volkow, M.D, quoted in What We Take for Granted

To loosen the tightening rubber band, to eliminate these distressing dreams, wouldn’t it make sense that I do a little real drinking instead of dream drinking? Just every once in awhile? The same small amount I do in my dreams? I wasn’t a huge drinker, only a bottle a night towards the end. Surely, both my days and nights would be eased if I just drank every once in awhile. That makes sense, doesn’t it?

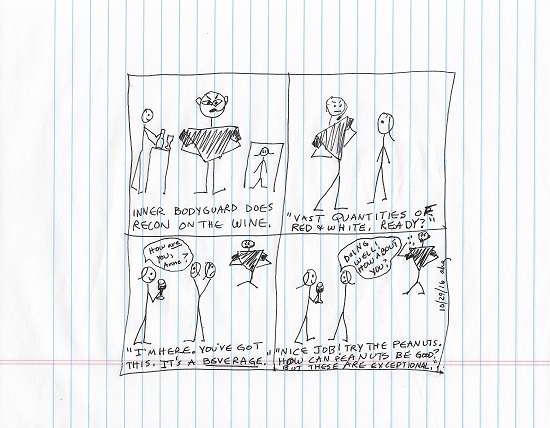

Within days of my sister inviting me to Thanksgiving at her house, I began to plan how, while I was helping set the table, I could pass by the wooden cabinet where the wine is kept, use whatever corkscrew was out because I am athletically quick with even the simplest version, palm the bottle (probably cabernet rather than merlot, but okay), take about twenty steps (yep, I mentally counted) to the hall bathroom, lock the door, and pour the wine right into my mouth from the bottle.

On second thought, why don’t I palm both the wine bottle and the corkscrew and then open the bottle in the bathroom? Oh, dear, that’s kind of like stealing, though, and wouldn’t it inconvenience my sister? Still, I would decrease my chances of detection. But, the pause in the bathroom to open the bottle feels like agony! I would want the bottle open before I got there so I could close the bathroom door with one hand and raise the bottle to my mouth with the other.

See how rationally I plan the irrational? I am such a bright, aware, educated, determined, willing person! Yet my thoughts plot substance use through theft.

Two months ago, I would be beating myself to a bloody pulp with a mental two by four for having these thoughts. My last theft was gum from the dime store in first grade. I never drank from the bottle when I was an active drinker. My family does not police my drinking. I did my best to do a little drinking – and couldn’t stop! After everything that’s gone down, after all the care so many people have given me to help me not drink, how could I possibly be thinking of drinking?! What is wrong with me?!

[T]he addicted person’s world is like a threatening virtual environment, a landscape calculated to pose maximal threats to their sobriety – in the form of drugs and drug cues – around every corner and lurking in every shadow. Yet the person playing the game must navigate this environment with a broken controller, such that no matter how hard they try to steer clear of hazards, their game-world avatar heads straight for the drug that will lead them to relapse.

– Nora D. Volkow, M.D, quoted in What We Take for Granted

Two months ago, I still thought addiction was my fault and, therefore, under my control. Any problems I had were because of me – I wasn’t doing recovery right. I wasn’t right.

In October, 2015, a groundswell of authoritative voices began to articulate what’s really up with addiction and how to treat it rather than repeating the folklore that predominates addictions treatment.

Today, I recognize my drinking thoughts as symptoms of the brain disease of addiction. I wish I didn’t have such a condition. But having a brain disease beats believing I’m a good person gone bad a millionfold.

We need to talk about these disorders [substance use disorder and mental illness] in a language that reflects their true nature; they are medical conditions, the origins of which lie in the person’s brain, and the effects of which extend into every part of that person’s life, and as with other illnesses, virtually always into the lives of the people who are touched by the patient.

– Robert Kent, J.D., and Charles Morgan, M.D., New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, quoted in The Fix

The science of addiction frees me from responsibility for my addiction and offers me responsibility for my recovery. How much time, heart and effort I have given to attempting to understand what went wrong with me!

Critics of our stance tell us we are absolving people of responsibility for their actions, when in fact we are doing quite the opposite. By delineating the true nature of the illness [substance use disorder], we can allow patients to get proper treatment for their illness…. [W]hen we treat SUD rationally in this way, rather than as a series of “volitional behaviors” that those afflicted should be able to stop if they were properly motivated, people affected by SUD can then take responsibility for their illness and get effective treatment.

– Robert Kent, J.D., and Charles Morgan, M.D., New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, quoted in The Fix

Thankfully, with what’s left of my volition and with enormous help and support from literally thousands of people, I have focused enough of my attention on recovery – rather than on addiction – to learn and practice what helps me stay sober and to become acutely aware of what threatens my abstinence.

Currently, being around wine – even thinking about being around wine – makes me want it beyond bearing. It’s not wine’s fault and it’s not the fault of people who drink wine. And it’s not my fault. My brain has become trained to want.

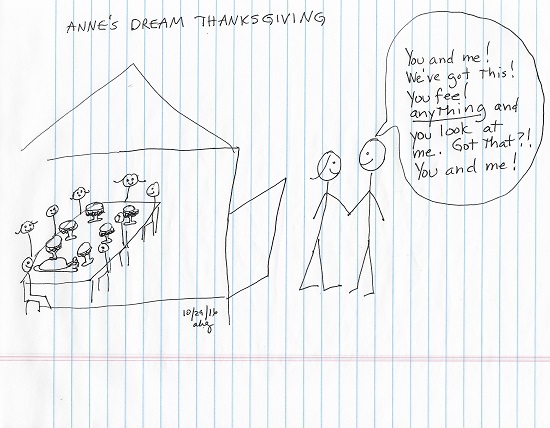

Last Thanksgiving, I was able to handle being around alcohol. This Thanksgiving? Days away, I’m already salivating – and not just for the exquisite feast my sister and brother-in-law will prepare for the family. I am so sorry I can’t go. And I’m so sorry what I have hurt and disappointed the people in my life. But the rubber band of the brain disease of addiction pulls me too tightly right now.

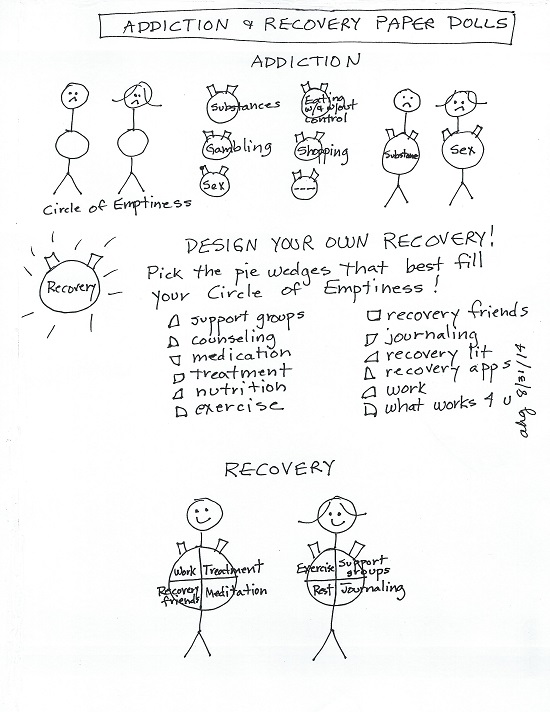

Addiction and Recovery Paper Dolls

Added 9/2/1014: I’ve received requests for a printable version of the cartoon so here’s a .pdf file: Addictions and Recovery Paper Dolls. Feel free to use and share!