“This study demonstrated that pre-COVID-19 diagnoses and understandings of grief are not sufficient to picture grief during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. These grief experiences are more complex and deserve further exploration.”

– Nierop-van Baalen et al., 2023

To begin, let’s define terms.

Here are definitions of grief and grieving based on those offered by Mary Frances O’Connor, Ph.D., author of The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Love and Loss (2021):

- Grief. After loss, grief is the complex, anguished, yearning feeling associated with love, attachment, bonding, connection, and belonging.

- Grieving is the process by which the heart, mind, and brain adapt and adjust to the absence.

Overviews of Mary-Frances O-Connor, Ph.D.’s research findings

In sum, the human brain has evolved to adjust to loss. The intensity of the love and bonding before the loss tend to align with the intensity of the grief after a loss. That is why “getting over grief,” “getting through grief,” and “healing from grief” may or may not be helpful directions. Is reducing or eliminating love – manifested as grief after loss of the loved being – truly the goal?

If a person can gently and kindly give the human brain time to re-navigate, love and grief may not be lessened, but the brain can adjust to the absence.

In my mind, I co-travel with grief. I am continuing on and I miss my beloved people and beings profoundly. Both are true.

Memories and rumination after loss

Distressing images may arise after loss. Although clinically termed intrusive memories, I wonder if the brain is attempting to cue a person to be cautious, attempting to help the person to remember in order to protect.

People who have experienced loss can find themselves analyzing or replaying the end, or rehearsing what they would do in the future. Although clinically termed rumination, I wonder, again, if the human brain is attempting to practice mercy, looking for loopholes, looking for different interpretations, looking for some way to ease the ache.

Giving time to intrusive memories and to replaying losses may inadvertently deepen memories through repetition, as if one were using a flashcard deck to memorize old hurts. Practicing shifting one’s attention – rather than following the narrative with its sad, but known end – may provide balm to the mind and heart and assist with helping the brain adjust to loss.

Intrusive memories and rumination are common after loss and cause distress and fatigue. To ease this distress, one can acknowledge the thoughts, acknowledge the human brain’s attempt to be merciful (“Ah, brain, that’s you trying to help me again”), and shift one’s attention to one’s values and priorities.

Other important, grief-related terms

Ambiguous grief: Simultaneously wishing for the person or being to die and free themselves and you – and wanting to hold onto them forever.

Anticipatory grief: Feeling grief now at the slow death of the person’s selfhood or the being’s identity, all the while knowing grief will occur again when the life ends.

Cumulative grief / compound grief: The complex feelings that occur after experiencing cascading losses in rapid succession without time to adjust to each loss. Experiencing cumulative grief is inherent to aging.

“The grief is the love.”

– David Kessler

Disenfranchised grief / Unacknowledged grief: From private losses, feeling grief that others may not believe is valid or may not understand.

Existential grief: Sadness experienced over the inability to find meaning from loss and a resultant sense of futility about the future.

Traumatic grief: Occurs in response to a death or loss that is sudden, shocking, alarming, and often involves a traumatic event.

Separation distress: Sadness, anxiety, and unease experienced from severing of bonds and the resultant neurobiological impact.

Secondary losses: Beyond a primary loss, additional tangible and intangible losses such as companionship, identity, self-concept, property or real estate, financial stability, social position, world view, and others.

“New losses bring up old losses”: Emotions, cognitions, experiences, and memories are experienced, conveyed and stored in the brain through connections and interconnections between neurons (neural pathways). New experiences may share similarities with previous experiences and activate the same neural pathways. When a loss occurs, similarities may be associated with – and be activated by – the type of loss, the feelings involved, or environmental cues. This intertwining of connections is why “a new loss brings up old losses.”

Other types of grief may include “overshadowed grief, cumulative grief, triggered grief, derailed grief, and conciliatory grief.”

Possible considerations

“[E]xperiential avoidance and rumination play a role in the persistence of complicated grief.” (Eisma et al., 2021)

“All grievers can benefit from support focused on understanding their grief, managing emotional pain, thinking about the future, strengthening their relationships…learning to live with reminders of the deceased, and connecting with memories.” (Meichsner et al., 2020)

“Grief will always be part of me, not as a superpower nor a thorn in my side but as a reminder that only a love so staggering in its intensity could produce an equivalent amount of sadness.”

– Rachel Daum

Here are the worst things people can say to others who are grieving (and to themselves). Here are the worst traits of people who try to help. (Please scroll to the bottom of that page to view the list.)

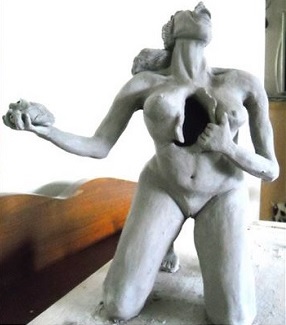

Image: “Untitled” by Trish Shelor White

Last updated 03/10/2024

This content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical and professional advice.