Updated 9/17/18: Here’s a new version of this post as a pdf.: Self-Care Checklist for People with Substance Use Issues. (Link opens in a new tab.)

. . . . .

To what extent do I agree that I have taken action this week on each recovery-supporting item suggested below?

I use the following scale to rate my agreement with each statement. If the statement does not apply to me – for example, I don’t use tobacco products – I write “N/A” (not applicable) on the line.

5 – Strongly agree

4 – Agree

3 – Neutral

2 – Disagree

1 – Strongly Disagree

_____ I have taken prescribed medication(s) at the correct time(s) each day and in the correct dose(s).

_____ I have attended medical appointments, scheduled a medical appointment, or checked my calendar to remind myself of upcoming medical appointments.

_____ I have been aware of my basic needs and have done what I can to help get my needs met. I am working on self-care.

_____ I have practiced sleep hygiene and I am working on establishing a regular sleep pattern for myself.

_____ I am working on establishing a regular schedule for myself to support my stability. I am working on radically accepting the paradox that imposing structure on my days gives me the freedom to be more present for them.

_____ I have engaged in daily physical movement and/or physical activity.

_____ I have centered my diet around nutrient-rich, recovery-supporting foods and eaten on a regular schedule. I drink plenty of water and help myself stay neither too hungry nor too full.

_____ I have monitored my consumption of caffeine and have maintained, reduced or eliminated it.

_____ I have monitored my use of tobacco products and have cut back when I could.

_____ I have become aware of my physical sensations, feelings, thoughts, and actions without judging or criticizing myself or my experience. I observe and identify patterns of feeling, thinking and behaving. I am learning mindfulness.

_____ I am becoming aware of what has my attention. I can engage, disengage, and shift my attention based on what I think is beneficial for me. I am applying what I’m learning and practicing it.

_____ I have listened for negative self-talk. I can separate helpful thoughts from unhelpful thoughts. I attempt to replace my negative thoughts with supportive thoughts.

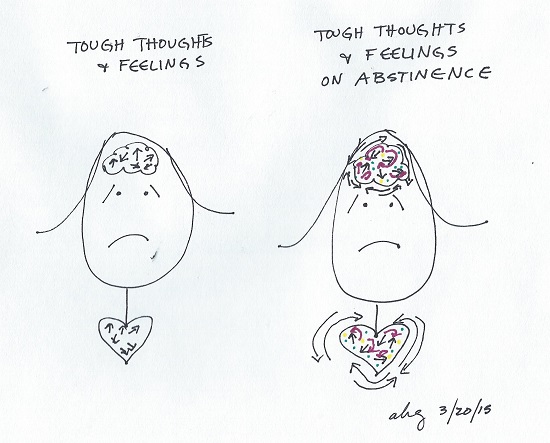

_____ I have become conscious of when I am experiencing strong sensory states, strong states of emotion, or many thoughts at once. I am aware of when I am in emotional or physical pain. I have used supportive self-talk and other tools to calm myself enough to be able to think before taking action. I am learning to tolerate distress and to regulate my emotions.

_____ I have attended individual and/or group counseling sessions.

_____ I have met with, talked on the phone with, or texted people who support my recovery. I am learning interpersonal effectiveness skills.

_____ I have worked on building social support, social connections, a social network, community membership, and a sense of belonging. I may have attended support groups such as SMART Recovery, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, and others. I may have joined community groups and common interest groups, volunteer organizations, sports teams and/or engaged in other group activities. I seek enough social interaction to feel connected and stimulated, but not so much that I feel overwhelmed and over-stimulated.

_____ I am exploring and discovering my preferences and personal interests. I am trying different activities, pastimes and hobbies to see which ones engage me.

_____ I am working on believing in my worth and learning my strengths. I acknowledge myself when I believe I can do something, say I will do it, and do it. I am learning to support my sense of self-efficacy.

_____ I am discovering purpose and meaning through self-reflection, self-discovery, and interactions with others. I am taking action on my purpose through paid work, volunteer work, and/or education.

_____ A recovery-supporting practice personally effective for me that I have done this week is: ________________________________________________________________________________.

_____ MY TOTAL. I can choose to create a total or not based on what I deem helpful to me as I discover the recovery path that is uniquely effective for me. I can change the wording of the items on this list, as well as add and subtract items as my understanding evolves. I can weigh some items more heavily than others and rank them in the order that’s most beneficial to me. I can use this list or not. If it seems helpful to me, I can track my totals over time.

It’s my life. Don’t you forget.

– It’s My Life, Talk Talk

. . . . .

How am I doing? How do I know?

What helps most people most of the time? Current data indicates that up to 98% of people with substance use disorders (SUDs) have co-occurring mental illnesses and significant numbers have experienced trauma in their lifetimes.

The list of recovery-supporting actions above is based on best efforts to distill current knowledge of evidenced-based practices, in priority order, that may assist many people much of the time with these challenges. At this time, no addictions treatment works for all people all the time.

I did not link the text above because every word could be highlighted and linked to multiple, readily-accessible sources. Where we couldn’t find research summaries, we created them. These links might be useful:

- Recovery-supporting foods

- Emotion regulation skills support addictions recovery

- Supportive self-talk (radical acceptance)

- Local addictions recovery resources, Blacksburg, Virginia area

- Reports on addiction from Handshake Media, Incorporated

The content of this post is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical, psychological or professional advice. Consult a qualified health care professional for personalized medical, psychological and professional advice.

Last updated 6/15/18