According to the just-world hypothesis, good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people. This thinking implies that people get what they deserve. If good things happen, people are acknowledged for their efforts. If bad things happen, people are to blame for incorrect or inadequate efforts.

Challenges arise when good things happen to bad people and bad things happen to good people. When reality interferes with a belief, people have to change their thinking to fit reality or tell a story about reality to fit the belief. The human brain has evolved to perceive reality the best that it can. When stories don’t fit reality, distress results.

People who have experienced hardship, adversity, and trauma can be troubled by the just-world hypothesis. In general, humans do the best they can at the time with what they know. When something terrible happens and the person was doing the best they could, the just-world hypothesis mandates that the person must conclude that what happened is in some way their fault, they deserve it, and are to blame for it.

About the future, people can start feeling helpless, powerless, and hopeless. If their best efforts resulted in that occurrence, what else might happen?! Both trying to control the future and giving up on trying to control the future are logical when one believes one causes what happens.

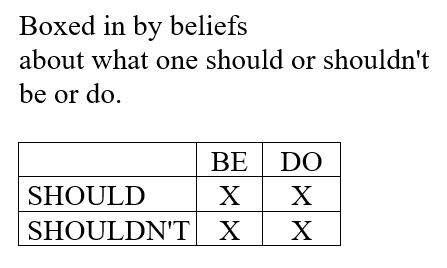

The just-world hypothesis can also lead to thoughts such as, “This can’t be happening,” “This shouldn’t be happening,” “Things shouldn’t be this way,” ”People shouldn’t be that way,” “I shouldn’t have to experience this,” and “I shouldn’t be this way.” To try to feel better from righting “wrongs,” people can strive to change the unchangeable, i.e. people and things as they are, and reality as it is.

On the one hand, believing one causes what happens gives one a sense of power, control, predictability, order, and hope.

“I can fix this! If I just think hard enough and figure out what to do and work hard enough, I can make this better!” Or, “If I just withdraw and hold still and don’t go out, I can protect myself from anything else bad happening!”

If one’s own efforts help in some way, this is reinforced and the person persists effortfully, even though they are likely to experience diminishing returns because people, situations, and reality as a whole are complex and one person has little chance of affecting any of it.

Self-criticism, self-judgment, self-reprimand, while painful, still result from holding on to the just-world hypothesis. If I hold onto the belief that I can have an impact on what happened to me, in the meantime, I must also hold onto the belief that I am to blame.

Under siege from self-blame, on high alert to execute plans and/or stay protected, and to sense signs of new threats. a state of alarm reigns. In this state of fiery activation and sensitivity, new hurts – smaller in magnitude than the older, harder hits – feel like the beginning of a wildfire in which everyone and everything will be lost.

People can tolerate the pain of carrying the just-world hypothesis only so long. I hypothesize that one of the signature, diagnostic traits of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – avoidance – is mercy. People might drink alcohol, smoke pot or eat gummies, binge watch TV, play video games, watch porn, shop online, eat, do anything, anything to mercifully give themselves a break from the fire or the threat of it.

On the other hand, the data is in. A person’s best efforts didn’t protect themselves or loved ones from harm. No amount of goodness or retreat can keep reality from happening.

I think one of the most excruciating, sorrowful moments in adulthood is realizing that we are not causal. Freedom from the hegemony of the just-world hypothesis is bittersweet. If we didn’t make bad things happen, we can’t make good things happen, either. Both are true.

It can feel heartbreaking to release the illusion that one’s birthright, one’s family’s standing, one’s morals, ethics, efforts, and achievements, all have such little power. The existential world view change required by this realization is massive.

Therapeutically, what might be helpful?

– With gentle self-kindness and the deepest compassion and humanity, see reality as it is.

– Become aware of feelings, thoughts, and sensory experience, data the human brain has evolved to assess in order to survive and thrive.

– Ask, “What are the facts?” and derive next steps based on facts.

– Restore one’s inner system to stability. Discover what individually and internally eases one’s inner system and do those. Meticulously find ways that are not avoidance strategies. Distraction is the opposite of attention. Attention is consciously chosen and given. Avoidance strategies may not have to be jettisoned, but they need to be absent from the inner system restoration effort.

– Acknowledge the human condition. Individual humans are subject to the human condition. This includes birth, death, and the vastness of possibilities in between.

Important. Thinking, “It could have been worse,” is based on a cognitive distortion. How? The human brain has not evolved to predict the future. What happened might have been worse, it might have been better, and it might have been no different. We can’t know. Believing one can know returns a person to self-causality, self-blame, and an incorrect assessment of the complexity of reality.

Further, in the universe of one person’s interiority, there is nothing worse than what happened. The person’s experience is true. Saying “It could have been worse” to people who have experienced hardship minimizes and invalidates their feelings, thoughts, and experiences and, in my view, is cruel.

– Gently acknowledge the context of the human condition. Try to find words for being part of the whole. Perhaps some version of this acknowledgement might fit one’s heart, mind, experiences, and perspective:

“In the 300,000 years of human history, among the 100 billion people estimated to have ever lived, what happened to me – or some form of it – happened to someone else. How excruciating, terrifying, and horrifying! How anguishing! How profoundly unfortunate this happened to me! And to others! How hard the human condition is! How brutal people and the world can be! And yet. I did not uniquely cause what happened to me. I was not singled out by the universe. My story is part of the human story. How my heart weeps for me and for all of us!”

– Know that the human brain is at its highest state of evolution. This is the best human brain that has ever been.

– Count on resilience and altruism. The concepts of “goodness” and “hope” are beliefs, not facts. However, although the human brain is incomprehensibly complex and diverse and difficult about which to make generalizations, current research reports that, in general, two things can be counted on in the human brain: a) to recover stability – to be resilient – and b) to be altruistic. Those sound pretty close to “hope” and “goodness” to me.

– Become aware of your values and priorities.

– Become aware of what you perceive is within your power to do.

– Do what you can.

In sum, with self-kindness and inner ease, powered by your values, directed by your priorities, with your resilient, altruistic brain, do what you can.

. . . . .

This post is informed by cognitive processing therapy, an evidence-based, therapy protocol for post-traumatic stress disorder, and by the brave, heroic people who have shared their stories of hardship with me.

I also want to acknowledge the bravery of the founders of cognitive processing therapy. In the second edition of Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Therapist Manual, released April 23, 2024, in Handout 11.1b, page 176, the authors address loss and trauma from mass shootings.

Holding the just-world hypothesis can result in self-blame, victim-blaming, and other-blame. For further exploration, consider these articles from Verywell Mind, Psychology Today, and Wikipedia.

The just-work hypothesis is considered a logical fallacy or a cognitive distortion. Of possible further interest:

- Checklist of Cognitive Distortions by David Burns, Ph.D.

- Common Cognitive Distortions with Simple Definitions

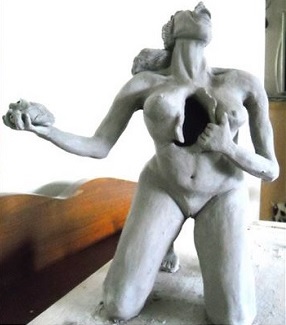

Illustration by Derek Zheng for Chapter 3 of Twig: 枝丫 by Anne Giles.

All content is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice. Consult a qualified professional for personalized medical, health care, and professional advice.