“Cogito ergo sum.”

– René Descartes

I was asked the other day, “How did you do it?”

“I don’t know,” I answered.

I do not know how I have stayed abstinent from alcohol for three years, having been unable to abstain for about seven years. I do not know how I got addicted to alcohol, how I stopped drinking, or how I’ve stayed stopped.

My inability to know nearly nullifies me.

When Dr. Leslie Mellichamp at Virginia Tech taught us René Descartes’s “Cogito ergo sum,” I felt the rapture of recognition. I toss my thoughts into the air like fall leaves, let them tickle my skin as they stream around me, lean back surely, delightedly, into their thick, crispy heaps.

I think, therefore I am.

When I started drinking, something began to decay. I remember writing a poem in honor of a former student’s graduation in 2008, feeling deeply, but straining to find words, baffled at the struggle to follow Coleridge’s guidance – “the best words in their best order.” It’s the last poem I ever wrote.

I cannot think, therefore I am not.

I have been in therapy with Dr. H. since just after my mother died in 2011. She astutely, indirectly, oh-so-carefully, oh-so-occasionally, brought up drinking. I remember her telling me in January, 2012, she had heard an NPR story about the CDC’s report on women and drinking. I Googled it. I took tests for problem drinking. I qualified. It would be almost a year, however, before I stopped drinking. That was three years and one month ago today.

I have chronicled my three years of abstinence as pretty much unrelenting suffering.

I cannot think, therefore I am not.

To counter that belief, the only thing I know to do is to do.

If I work, and, through my work I help, therefore I am, if only a little bit.

The work that came my way in the third year of my sobriety was helping people struggling with addiction. No matter what I did, I could not help.

I cannot help. Therefore I am not.

Suffering threatened a bonfire.

Between sessions in October, I shared this thinking with Dr. H. in a piece of writing. She speaks eloquently and, of course, grammatically, but this is what I remember she said at our next session:

“You think wrong. Here’s how you think wrong. Here’s why you think wrong. Here’s how to think differently. If you don’t think differently, you will continue to suffer.”

I was aghast. Confrontation withdraws heavily from a relationship’s bank account. Her years of oh-so-carefully, however, had built a bountiful trust deposit.

Hmm. I think, therefore I am. If I think wrong and can right my thinking, might I exist again? Might I save myself from the flames?

She essentially said I had to accept it all. Everything that had ever been said or done to me, everything that I had ever said or done, I had to swallow the ocean of it into my own gut. And keep it down.

I’ve been at it since. I spit mouthfuls of acceptance at anything that’s even hot.

Then I glug it back in.

I don’t know how to get or stay sober. I do know how to accept that my ability to think – what I cherish most about being me – is lessened by alcoholism, perhaps forever.

I think well enough, therefore I am enough.

I’m not a fan of that. But if I accept it, I simply feel better.

I think, therefore I write. Even if it’s only good enough writing.

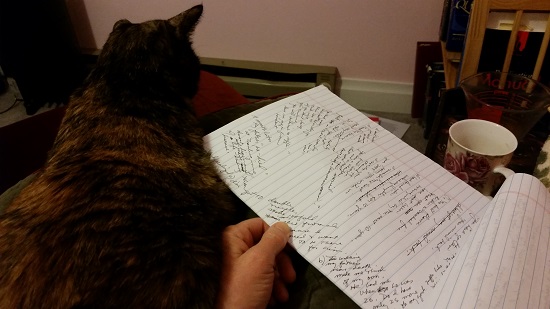

This post began on a lovely leaf of lined, white paper.